Cleo Childs released her spoken word poetry album, “Moving With” in May 2024. And her book, also called “Moving With,” is soon to be released. Both projects are the culmination of years of writing about the journey of grief Cleo experienced after losing her mother to Alzheimer’s when she was 28 years old.“Everyone has told me, thank you. I got told recently that, if it comes out and everyone hates it, that is totally fine with me because someone told me in a beta read report, she said, I feel like you sat with me in my grief and you held my hand.” Cleo Child

Cleo’s mom was an English major in college and her grandmother, who is also one of her editors, was an English teacher for 30 years, so she came naturally to writing as a grief processing tool. With her work, Cleo hopes to show the path her grief took from having her mother, losing her mother, and the peace and acceptance she feels now. She also hopes to authentically and honestly look at what her grief felt like so other people going through their own grieving don’t feel alone and have a sense of community.

You can learn more about Cleo and her various projects at cleochilds.com.

WEBSITES:

IF YOU LIKE THIS EPISODE, YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY:

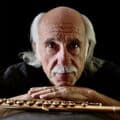

- Michael Mason, Musician-Session 3-Episode #340

- David Paul Kirkpatrick, Former President of Paramount Pictures-Episode #332

- Jimi Fritz, Musician-Filmmaker-Author-Episode #305

- Stephen Cole, Musical Theatre Writer-Session 2-Episode #298

- Dr. Niyi Coker Jr., Professor-Director-Episode #294

- Rosanna Staffa, Playwright-Author-Episode #290

- Adryan Russ, Composer-Lyricist-Episode #204

- Sarah Bierstock, Actress-Playwright-Episode #171

On today’s Story Beat:

Cleo Childs: everyone has told me, thank you. I mean, and that’s the thing, is that if it comes out and everyone hates it, that is totally fine with me because someone told me in a beta read report, she said, I feel like you, you sat with me in my grief and you held my hand. Done. Success. Everything else doesn’t matter. This is Story Beat with Steve Cuden. A podcast for the creative mind. StoryBeat explores how masters of creativity develop and produce brilliant works that people everywhere love and admire. So, join us as we discover how talented creators find success in the worlds of imagination and entertainment. Here now is your host, Steve Cuden.

Steve Cuden: Thanks for joining us on Story Beat. We’re coming to you from the Steel City, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. My guest today, Cleo Childs released her spoken word poetry album moving with in May 2024. And her book, also called Moving with, is soon to be released. Both projects are the culmination of years of writing about the journey of grief Cleo experienced after losing her mother to Alzheimer’s when she was 28 years old. Cleo’s mom was an English major in college and her grandmother, who is also one of her editors, was an English teacher for 30 years. So, she came naturally to writing as a grief processing tool. With her work, Cleo hopes to show the path her grief took from having her mother, losing her mother, and the peace and acceptance she feels now. Cleo also hopes to authentically and honestly look at what her grief felt like. So other people going through their own grieving don’t feel alone and have a sense of community. You can learn more about Cleo and her various projects at cleochilds.com so for all those reasons and many more, it’s a truly great privilege for me to welcome the superb poet Cleo Childs to Story Beat today. Cleo, welcome to the show.

Cleo Childs: Happy to be here.

Steve Cuden: It’s a great privilege to have you here. So, let’s go back in history just a little bit. I know that a lot of what you write is historic. It’s about the past bringing it forward. So, tell us a bit about your history. How old were you when you first noticed poetry and words and writing and that sort of thing?

Cleo Childs: Well, my grandmother beat me over the head with, uh, a thesaurus when I was a kid, so I loved, I loved words. That was one of my greatest gifts as she gave me a dictionary in the Source and everyone else has, you know, like Beyblades or Pokemon, which I also had. But I also was the really fun kid that carried a thesaurus when she was 4 years old. And so I learned I love words. My grandmother, uh, gave me a love of words. And my mother, being an English major, also gave me a love of words. So, I grew up loving words. And I read, you know, I had Chicken Soup for the Soul, the entire series at the age of 8 or 9. So I had all the books, and I would just read Chickens over the Soul. And I had a book closet. I was very fortunate. She would take me to, like, thrift shops and she would just go and, you know, walk around and go get clothes. And I would just sit in the bookstore area of the shop, and I could pick out, you know, five books for like a dollar each. And I would go and just pick out my favorite ones and then I would Terry. And so, like, I amassed a huge collection of books. I had more books and clothes eventually. Um, and then I went off to college and my grandmother labored, labored to make me a good research paper writer. Every time we had a research paper, I would write it. It was awful. Then I would send it to grandma, Grandma would edit it, and then I would edit it. We would be on the phone for like two hours going over all of my edits and I would have my edited version. Then I would take it to my English teacher who would also edit Grandma’s edits that I took in. Then I would take her edits back, put it in, and then I’d go to Grandma, and I would do this four to five times for each research paper. So, by the end of freshman year, I became really good at research papers. But when it comes to creative writing, I never did creative writing. I think that the only reason I went into creative writing is because I was very fortunate to have the gift after my mom passed, to have two lines appear in my head at about 2 o’clock at night, maybe about three to four weeks after mom passed.

Steve Cuden: Two lines of writing, two ideas.

Cleo Childs: It was just two lines of writing, and they wouldn’t go away. And I went downstairs, and I went to a little green notebook that I put all of my favorite quotes from the stoic philosophers in, and I just wrote them down. And that was the only thing that made it feel better up to that point was just writing.

Steve Cuden: But you were an inveterate reader. You read a lot.

Cleo Childs: Oh, yeah, I love to read. I never wrote. I never imagined myself as a writer. I’STILL coming to terms of the fact that I am a writer, you know, I think, honestly. But I had these lines, and I wrote them Down. And then I felt better. It was the first thing that made me feel better. So, I kept writing and I wrote in a little grey notebook. I’m looking at it right now. And I wrote solely for myself. It was the only thing that made me feel better.

Steve Cuden: So, I’m curious, when you say it made you feel better.

Cleo Childs: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: What was it? Were you sad or unhappy or. When you say it made you feel better, where were you that you needed to feel better?

Cleo Childs: I was in deep, deep, deep, deep grief after my mom died.

Steve Cuden: I see.

Cleo Childs: Uh, she got diagnosed and I was 21 years old. And then of early onset Alzheimer’s. And then she died suddenly at 28. So, she was supposed to have two more years of life expectancy. And I got the call on Halloween of 2021 that she passed away. And it destroyed me. I had no idea how to function. I was just as in deep grief as one could be. Uh, I was like, disassociating. It was just really. I couldn’t imagine. I couldn’t imagine this to happen because I thought that I had done anticipatory grief really well. So, I had, you know, grieved my mother.

Steve Cuden: Explain for the audience what anticipatory grief is. By the way. Just so you know, my mother went through four and a half years of, um.

Cleo Childs: I’m sorry, it’s.

Steve Cuden: I understand it. But what is anticipatory grief?

Cleo Childs: Anticipatory grief is the idea that you are losing someone and you’re grieving the loss of them while they’re still alive is how I define it.

Steve Cuden: Mmm.

Cleo Childs: You also go through many losses. Many and many losses. So, the one that I kind of put in the book is this loss that was so heart wrenching to me is it makes me still choke up, is I knew that my mother would never say my name again. And I imagined that day was coming the second that she got given up the ar. Early onset Alzheimer’s diagnosis. I was like, she’s never going to say my name again. And it terrified me. And so, after every end of the conversation that I had with my mom, I would say, is today the day that she forgets my name? And. And eventually that day came, and I just wept. It was one of the. It’s one of the worst days of my entire life. And then I had to become okay with being a nice lady. So not only did I lose my relationship with my mother, I lost my relationship as a daughter. And I had to gain a new title of being a nice lady. And I also lost her ever Saying my name again. And my mother was wonderful with names. I love my name. So, my real name is. My legal name, I should say is Reese Cleo. So, Reese is my first name. So, if I do refer to me as, you know, Reese, it’s it me. I came up with the idea of having a pen name because my last name is Zahner. And everyone my entire life could not spell or pronounce my last name. I remember being in the fifth-grade graduation, and I told my principal, it’s Zahner, and he called me Zaner. And I remember indelibly being like, fifth grade. I was like, this isn’t going to bode well if I want to be a creative. Like, I. I was like, I have to change my name because no one can say it, and no one could spell it. So, when I was about 15, 16, I had this idea that if I was going to go into something creative, I would have to get a pen name. And I was bored. And I thought about it for, like, I don’t know, like a day to, like two weeks. And it came up with Cleo Childs as being my pen name. But my mother, I love my name. My mother spent so much time on my name. She was wonderful with names. And I knew that, uh, she would never say my name again. And so anticipatory grief to me is having a person and then re like falling like sand through your fingers.

Steve Cuden: One of the things that a lot of people that have never experienced Alzheimer’s don’t understand is you are actually losing the person. Not the body, not the physicality that’s still there. But you lose who they are because they lose who they are. So, they stop seeing what you and I see. They see things that are delusional. And they also lose memory of who people are and what things are and whether they’ve done something or not, that you’re losing the core of what we think of each other as his people. We lose that core, but the physicality is still there. So, the humans there, but it’s hard to talk to them because they’re not saying things that make sense. Is that correct?

Cleo Childs: The image that comes to my mind is it’s like having a vase that used to be full.

Steve Cuden: Mmm.

Cleo Childs: And now you just have a vase.

Steve Cuden: That’s very good. That’s a good image. And that’s what it is. It empties out. You’re still looking at the same person, but it empties out like a vase. All the interior, all the personable part of a person. So, yeah, it’s really, really hard. It’s really, really hard. What then attracted you to poetry, and why did you turn to poetry? Not writing a novel about it or, uh, a nonfiction book about it. Why poetry?

Cleo Childs: I love writing prose, but when I first started to write, I did not write prose. I wrote a poetry because the first two lines that came to me were the first lines of a poem. And so, I kind of just went into writing poems solely for myself. And I think it was the pure expression of getting something in me that was these emotions and these feelings of turmoil and despair and grief and. And putting them on the page as if to say that I was kind of relieving myself of them and I could process them. It was a processing tool.

Steve Cuden: Do you think of the poetry that comes to you coming from a spiritual place?

Cleo Childs: I think it doesn’t come from me, if that makes sense. Like, from my conscious self.

Steve Cuden: So many creative people, many geniuses, say that what they come up with comes through them from somewhere else. Like you’re a conduit for it.

Cleo Childs: Exactly. That’s exactly what it is. Because I could never think of the things that I write. And in fact, I have no idea really what I’ve written until I’ve written it. And then I go back, and I see what I’ve written, and I go, ooh. I get so excited. I’m like, look at me. That was a real good thought that I had. But I have. I can’t claim it, if that makes sense.

Steve Cuden: So, it’s more than an epiphany. It’s. It’s beyond epiphany. It is. You’re actually channeling it in a way.

Cleo Childs: Yeah. When writing this moving with book, I could feel when I had to write, which I don’t know if anyone else has to do that. I feel like, physically there was a place in my body, it’s like kind of around the sternum that would get a pressure, and it would not go away until I had. Until I wrote and then I could go to sleep. And it usually happened when I was, uh, trying to go to sleep, which was highly annoying because I was trying to go to sleep, and I’FEEL this pressure on my, like, my sternum. Um, and I was like, no, not now. And it wouldn’t go away. And then I would write, and I would just get really frustrated, and I would just be like, fine, I’ll just write something. And all I would write, and then I would go to sleep, and I wake up the next morning, and what I Wrote I really liked. And I was like, well, that’s interesting. But I can’t claim what comes to me, if that makes sense. Like, I feel like a conduit for it because I can’t explain it. I use words. Sometimes the words even I go. I have to go like, double check the meaning of the word. Because I’m like, I think this is the word that I’m. I think this word fits and it always does. But it, it comes through my subconscious, or it comes through, you know, I can’t consciously claim it.

Steve Cuden: Well, but you should claim it because it’s you who writes it and it’s given to you from whatever source it’s coming from. Uh, whether it’s the universe or God or whatever you want to call it, it’s coming to you and through you. So, it’s yours?

Cleo Childs: Yeah, it’s mine in the way that I wrote it. But I feel like I can’t claim it consciously, meaning that it’s my writing. But I feel like to say that it was me as me writing it is not necessarily the case.

Steve Cuden: You’re saying that you can’t sit down and make it happen. It has to come to you when you, when you’re inspired.

Cleo Childs: Absolutely. If I sit down and try to write something, it is not good. What I do is I have to turn my brain off. And apparently, I was looking at, um, different writers and Ray Bradbury said the same thing. He said, you cannot think. And I went, ray Bradbury gets it. You do. I turn my brain off and I don’t think, I just do. And then I see what comes out. I kind of call it like a fountain. I kind of feel like I just turn the fountain on, and I see my, my fingers are the fountain, and I see what comes out of the fountain, but I cannot, uh, that’s as far as the metaphor goes in my head. But it’s. It’s like a spring. It feels like a spring that’s kind of in my fingers. Spring water.

Steve Cuden: Do you go into a zone kind of?

Cleo Childs: Uh, yeah, it might be like a flow state. It’s mhm. I kind of go into this flow state. I’d never look at what I’ve just written. I always just think, what is the next thing? And I write that. And then once I get to a stopping point, I go back, and I see what I’ve written. And usually I go, When I’m not thinking, I go, ooh, that’s good. It’s when I think that I go, gotta work on that one.

Steve Cuden: So, you have to, in a way, like a fisherman. You’ve got to cast a line into the ether and hope something catches onto the hook. And so, you have to patiently, uh, wait for it to come. Is that right?

Cleo Childs: It’s funny you mentioned that. So, I wrote a poem. I don’t. It’s not edited right, so I don’t judge me on it. But I wrote this as if I was trying to explain one time to my husband what it was like to be in my body when I go and I write. You can keep asking me questions while I look at it.

Steve Cuden: Did you go to school to learn how to write poetry, or did you just do it?

Cleo Childs: No, I just did it.

Steve Cuden: Did you study poets?

Cleo Childs: I studied poets. I actually studied more than poets. I studied songwriters. To me, songwriters are. They did something that. I think that for me was emotional. I felt an emotional tie. And I studied Dylan. I studied a lot of, uh. Like Dylan Cohen, Joni Mitchell, uh, Jason Isbel are my favorites. My four that I would really study. And then I studied Townes Van Zant at the end of it. The reason I study them is because they touch something within me as if to say. And. And I think that. And I study. And I love Sylvia Plath, and I love Anne Sexton and, uh, the Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. So, I actually read a paper about that in college, but those were the ones. Okay, Here, I found it. Ha ha. Okay. So here we go. I stand in the stream, my ankles wrapped in Poseidon’s fingers. Rod in hand, I cast it out, sailing over my skull at lands with the plop in my mind, waiting patiently for my thoughts to bite, to be dragged out and fillet on the page. My husband asks what I’m doing as I stare at the empty page. I’m going fishing, I tell him. Befuddled, he’d leaves me alone as I return to my task.

Steve Cuden: That’s it? That’s your particular process? Which is.

Cleo Childs: That’s my process.

Steve Cuden: It requires you to be patient. You have to wait for it to come, because it’s not going to come every single moment of every single day. Now, by the way, Dylan. Recently I saw an article with him from not too long ago, but not. Not that recently, in which he was asked, are you still able to do what you did back in the day? And he said, no, I know.

Cleo Childs: It freaked me out.

Steve Cuden: So, whatever that muse that was coming through him, and he’ll tell you, just like you, that he has no idea how he wrote those songs. They just happened. And so, you and Dylan are Sort of on that same plane of it’s got to come through you, you. It’s got to be that inspiration. It’s not something that you conjure up. It just happens to you.

Cleo Childs: Yeah. I think that I read a story about the difference between Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan. Cohen spent years writing Hallelujah. He spent; I think it was 80 verses. Years, years. And Dylan wrote Mr. Tambourine man, which is my personal favorite. And uh, I forgot how long it was, but it was like nothing. Right.

Steve Cuden: Well, many of the great rock and roll songs and songs of that era. Many, many and to this day actually are written in no time flat.

Cleo Childs: Yes.

Steve Cuden: The artist goes right straight through, and they blow them straight out. And that’s very common. M and that they don’t labor over them at all, but they wind up being huge for the public.

Cleo Childs: I think that’s the thing is the things that I labor over are not good for me and I go back to them when I turn my brain off. So. So the book is 13,000 words. It’s short, but I. I made it short because I said everything I wanted to say within 15,000 words. And then I edit it down to 13,000 words by taking up fillers and combining words and editing. And I wanted it very specifically to be short because I wanted to take someone on. On the emotional journey of what my grief was like in one sitting. And that was the goal, to take you on the emotional journey. And if I knew that if I made it longer, not only did I not have anything to say and everything would be filler, but it wouldn’t be concise enough that you could go on that emotional journey. And one sitting, I wanted you to do it in one sitting. And there were certain things where I would write it and I would go, mhm, no, that’s not, that’s not it. And then I realized in my editing process, what I do is I go for a walk, and I turn off my brain and I listen to music, and I bring my phone with me, and I edit and I edit as I walk. My brain, I turn my brain off and then my brain goes, that’s a better word for that. And I go, thanks brain. That is a better word for that. So, then I pull out my phone and I delete the word, and I put in the new word and I just kind of turn my brain off and I let my brain tell me what it needs to do.

Steve Cuden: So, you don’t use tools like a thesaurus or a rhyming dictionary or something. Like that.

Cleo Childs: The only tool I used was something called the Hemmingway Editor. I don’t like AI I give AI one pass. One pass for me. It’s called the Hemingway Editor. And what it did is it told me where my sentences were too complex. And they gave it a readability score. And I went, okay. In the editing process, I would go in, and I would re put all my stuff in the Hemingway Editor. And it would tell me, is it too complex for a reader? I would make my sentences very clear and concise. And I used the Hemingway Editor. That’s the only tool I ever use. I don’t use rhyming dictionaries. I don’t use the sources. If anything, the only tool I use is I use the source or a dictionary to tell me what is the meaning of the word. To confirm that my meaning of the word is correct. Because it came to my head, and I want to make sure. And it goes, yep, that’s the right word. I’m like, thanks, dictionary. But I don’t go out and I search for words. I just sit there, and I wait for the perfect word to come up. And I know if I wait long enough, it will.

Steve Cuden: I think that makes you kind of fortunate. I think a lot of writers do not have that at least not conscious ability of it. Of doing just exactly what you’re talking about. I frequently have to turn to other sources to help me along. And I’ve written a lot of lyrics in my life. And I have to turn to a rhyming dictionary every once in a while, because I can’t think of a word that’s helpful. But you, on the other hand, are. It’s a little different because you’re writing this very, very intensely personal poetry.

Cleo Childs: Yep.

Steve Cuden: And that intense personal thing is a little different than writing something that is not necessarily personal. I mean, may. It’ll have a personal element to it. But when you write. For instance, journalists don’t write personal stories. Often, they write what they’re dealing with in front of them. And novelist go to Ray Bradbury. His stories were often not personal, though there was personal feelings and emotions in them. I’m curious what is a weird question, but what makes poetry poetry? I’m thinking it’s a hard question.

Cleo Childs: I know. I’m, uh, gonna go not with the technical term because I don’t feel qualified to give the technical term. I’m gonna go with what my. What my personal belief is. It’s saying something beautifully, concisely, in a way that translates in a very specific way an emotion or Feeling or an idea into someone else’s brain using a format that is consistent. I know there’s debate about lyrics versus poetry, right? Dylan famously won the Nobel Prize. And everyone’s like, well, is he a poet? And I say, to me, it doesn’t matter, quite honestly, because I take inspiration from the fact that lyrics and poetry, to me both make me feel something in a very similar fashion, using a stylized format. They make me feel and they emote and I. They connect to me in a very specific way. And so, when I look at song lyrics, because I really looked at Sylvia Plath and Sexton, the J Alfred Prufrock, the Love song of J Alfred Prufrock. And I looked at all of these amazing writers who I connected with. And I looked at the lyrics without looking at the music. That’s how I read there the work. So, I would look at Mr. Tambourine man, and I would just look at how the vowel sounds. So that’s how I taught myself vowel sounds as I would look at. And, uh, I developed an ear for myself by reading Dylan and figuring out, well, why did Dylan use the. Why does it sound pleasant to the ear? And I taught myself by looking at Mr. Tambourine Man. I think it’s a wonderful exercise in vowel sounds. And I’d say, well, the reason I use this word is because this vowel sound goes out here. And I figured out how to be able. So, when I try to create words that go and sound to each other, what I do is I figure out what the vowel sounds or the consonant sounds. What is the sound of the word? And then I go like, for example, if I was to say little, I’d, uh, say l. It maybe turtle might rhyme with that. Little turtle would sound nice next to each other, right? So, I just came up with that on spot. But my point is, it’s. I would let the consonants, or the vowel sounds tell me what the next word should be. So that’s why, like I’ve initially had cold. A, uh, cement floor does not sound better. So, I changed it to cold concrete floor. Because of this. The cold concrete floor sounds with the o sounds. Sounds nicer together than a cold Cree floor. So cold concrete floor flows better. Dylan taught me how to do that. Or I learned it from Dylan.

Steve Cuden: Well, the songs are a specific thing where it has to be in with the rhythm and the beats of the song of the music. And as a poet, you’re not required to do that. And if you do do that, I think it makes it more rhythmic and feels a Certain way flows a certain way. But there are plenty of poets out there who never get anywhere near that kind of thing. I’m thinking in particular of E.E. cummings. I mean, those are not lyrics. Yeah, Ogden Nash. Ogden Nash could be lyrics. You know, it’s those kinds of different things.

Cleo Childs: To me, it’s the most fun way to write. I guess that’s why I do it is I’m selfish in that way. To me, it’s joyous is a good thing. It’s joyous to figure out, oh, what is the best next word? What is a word? Concrete and cement say basically the same thing, but one sounds better next to the other one. So, to be able to come up with certain words and figure out, well, is this the right word? Yes, it’s doing. It’s the purpose of it. But is there a better word that sounds nicer and it’s more pleasing to the ear? And so, I love, like my brain went. You know, I wrote a Cold Concrete Floor about three years ago because all the poems in it are basically poems that I wrote in grief. And I put them in, and I’ve updated some of them or changed some of them. And I went in my brain, I was wanting to walk. My brain went, nope, it should be U. Uh, not cement, should be concrete. And I was like, good job, brain. That is right. So, I didn’t come to that conclusion. But my brain, I kind of also do this thing where my brain works on it in the background, and I let my brain work on it in the background and I go do something else. And then inevitably I go on a walk. And on my walk, my brain will tell me what it’s worked on in the background and I go, oo, that is right, brain. Good job. As if to say, I don’t feel like it consciously comes to me. My brain works on it and then it brings it to my attention and then I input it in.

Steve Cuden: Well, you’ve tasked your computer coming up with a solution, and the computer cogitates for a while and eventually spits it out. Yeah.

Cleo Childs: And I just walk until a computer spits out an idea and I’m like, o, good job, brain. That would have been bad if it was that way. And I just am very thankful. I say, thank you, brain, and then I put it in.

Steve Cuden: So, you mentioned a moment ago about what you think makes poetry poetry, and you used the word beautiful in it. Were you talking about that? It’s the wording has to be beautiful, or the sentiment has to be beautiful, or can a, uh, poem also Use ugly words and somehow make that beautiful. How does that work?

Cleo Childs: I think it’s the intentionality behind it.

Steve Cuden: Explain.

Cleo Childs: For example, right. If I. The thing that’s coming up for me is Lady Lazarus by u. Uh, Sylvia Plath. I love Lady Lazarus. She uses a lot of Nazi imagery, Right. And she’s using that to be provocative. Right. And you look at it and you. There’s a lot of debates on Lady Lazarus. Her intention, though, behind it was very specific as that’s what I think is like, one of the ugliest things that you could do is be able to, you know, equate that. That’s horrible. And it’s in her intention. If you look at her intention of it within the piece, it makes sense because she’s using it to be ugly to demonstrate the ugliness that she feels sorts her father for dying early. Right. And so, I feel like there is an in the intentionality behind that. I feel like there might be beauty in the execution. I think that’s what I mean. It’s not only the beauty and the intentionality, but beauty and the execution of the idea and the intent behind that idea. And I feel like the execution can be beautiful.

Steve Cuden: Do you believe that poetry must be truthful and honest, or can it be the opposite?

Cleo Childs: I know what poetry speaks most to me, and that is the poetry that matters, uh, that’s truthful and honest. The poetry that resonates is always truthful and honest. And I feel like there’s something that is in, like, the lizard part of our brain that can tell if there’s falsities or not. And it turns off and it does not connect as well when there’s falsities in between it. I think that there is when someone is honest and truthful, and it could be truthful to themselves. Right. I think that something else is. So, my level of honesty and truthfulness within myself might be different from someone else’s level of truth that they can have with themself. But if it’s at the maximum capacity that they are telling their own truth, it resonates because it’s being honest. I think that it is being honest and true to their experience with as much truth and honesty as they can give.

Steve Cuden: Well, I think sometimes poems can be. They can cut straight through in very few words and cut through and give you the bottom line on something without you going through a whole lot of explanation.

Cleo Childs: It’s wonderful. And I think too, is my favorite ones, and I did very intentionally in the book and in all the poems is I do not tell you how to feel because quite honestly, I don’t know how I feel. Right, right. But I think that there are some commonalities between what I feel and what someone else feels when they receive it and when they interpret it. So, you know, if I wrote something that I’m feeling angry with, someone might say that that’s bitterness or angry, which is a similar emotion. Someone wouldn’t go in and interpret it as being happy. Right. And I think that leaving up that interpretation is really important because that’s what I believe art is. So, I thought about, I’m really fun at parties. You’ll find this out. Because I thought about for three days, what is the meaning of art? Random strangers. I was recording an album, and I was like, what is the meaning of art? I thought about it for three days. So. And I would just go up to people and be like, you know what the meaning of art is? And I finally came to the conclusion for myself what the meaning of art is. The meaning of art is it connects the creator, which would read me to the divine when creating it, and it connects the receiver who receives there to the divine when they receive it. That is my meaning of art. I’m connected to something bigger than myself when I create art. And I think that when I receive art, I’m connected to something bigger than myself when I receive it because the person was connected to something bigger than themselves when they created it. And that it took me three days to cope with that conclusion.

Steve Cuden: Well, I think that that’s a spot on conclusion. I think that art is bigger than the individual.

Cleo Childs: Mhm.

Steve Cuden: And bigger than the creator. And if you actually create art, it is theoretically. Not always, but I think theoretically and mostly universal.

Cleo Childs: Yes.

Steve Cuden: So therefore, it’s for all. That doesn’t mean everyone will get it or enjoy it or appreciate it, but it is there for all. And once you’ve created something and someone else takes it and listens to it or reads it or watches it, whatever it is at that moment ceases being the creators. It becomes the person who’s perceiving it. Yes. It becomes theirs.

Cleo Childs: Yes.

Steve Cuden: Because they perceive it in their way, not necessarily the way that you created it.

Cleo Childs: Yes. And they receive it through the lens of that. Of their life experience.

Steve Cuden: Yes.

Cleo Childs: Which is different from my life experience, of course.

Steve Cuden: And um, they may be at different stages of life and perceive it completely differently than you.

Cleo Childs: And it’s really been interesting. So, with the book, I’m in the beta reading phase, so I have beta readers read it and it’s really important to me. And I don’t know if other authors do this, but it’s incredibly.

Steve Cuden: This is your prose book.

Cleo Childs: This is my prose book. It’s incredibly important to me to have readers read it before I release it, because I want it to be in communication with the reader. And there are. It’s really interesting to see the reader feedback because I get reports about. And people connect to different things. Someone was saying that they are going and becoming a caregiver, and they really appreciated the caregiver guilt that I felt and the frustrations of being caregiver, because that’s what they are connecting to, because that’s where they are. Someone else said, you know, they lost, um, a younger brother, and they really felt isolated, uh, when they’re around other people. And that’s what they connected to, is the feeling of isolation. I put out. Someone else said that, you know, ye. I talk very openly about the fact that I became dependent on alcohol after my mom passed. And they’re like, I did the same thing. Right? And it’s. If you look, it’s the same piece. That’s the same art that I’ve created. But everyone, based off of their life experiences and based off of their own, where they are in their lives, connects to different pieces. And it resonates differently with everyone. I think that’s the beauty of it. And I think, too, the beauty of it is that for me, it is all true and honest, and the entire piece resonates with me. But other pieces will resonate more with other people because of what they bring themselves into it.

Steve Cuden: I think that’s spot on. You brought up that you were recording. Were you talking about recording Moving with.

Cleo Childs: Yes, when I was recording. Mo with. I also have two other poetry albums that I’ve recorded that I will be releasing over the course of, you know, the next couple of years.

Steve Cuden: Wow.

Cleo Childs: I’ve already recorded them, so.

Steve Cuden: So, I sort of enjoyed reading the poems along with you reading it aloud. I was reading what I was hearing, uh, uh, which is always kind of interesting because we don’t typically do that. We typically will watch a TV show or a movie or something or play. And we’re not reading along with it. We’re just enjoying what we’re getting. But I found it fascinating to read the words while you were speaking. Tell the listeners a little bit more about your mom and why you were so motivated to put out an album first and then a book based on the. On her and your feelings in this poetry. Tell us about her.

Cleo Childs: My mother’s wonderful. My Mother is kind, she is gentle, she is good. She is one of the kindest, most gentle people. And I lost her. And I think that, you know, I was talking to a friend of mine, and someone said, are you still in grief? And I think what I said to. It’s not. What I think I did say to them is I said, I’m not in grief. I’m in mourning. I will forever mourn my mother. And I wrote these poems for myself. And it was funny how it happened is I wrote another poem, and I went to a record. I was trying to get better at songwriting. I got inspired by songwriting, and I went to a record producer in Nashville, and he said, you’re really good. And I was like, what? Because I was writing solely for myself, it never occurred to me to produce or never occurred to me release them. I was just trying to, for myself, get better. And he said, I’ll produce you. And I said, you’ll do what now? What never occurred to me. And I thought about it, and I went through. And I was editing this other album, which is some of the stuff is going to be on other albums that I’ll release in the future. And one of my editors and I would read her some of the stuff I read about mom at the beginning of our sessions. Like this. I’m kind of working on this, but this is really what I’m focused on, because this is what I brought to the producer. And she goes, your stuff with your mom is your best stuff. Tell me more about that. Tell me more about your mom. And I realized, you know, at the time I was said if I only had one album to make because I was never planning on making more. I said I would tell the story about me and my mom. That’s the thing that’s important to me. If I could have one thing, that’s what I want to leave behind. And I also came the conclusion of why should I do it? Right? It’s very vulnerable to put yourself out there, particularly the story of something, you know, so vulnerable is grief that you’re opening yourself up to be misunderstood. And I realized, because my mother was a helper, above all, my mother helped, and I thought it could help someone. And so, I released it, not knowing if it would. But I released it on the. On the off chance that it could help so someone not feel so alone in grief and the way that I did because someone else said something. And when it came to writing the book, the book is a series of vignettes. I had vignettes that I was really proud of. And I realized that I had more to say than just the 12 poems that I wrote on in the album. And it was more of a personal project to me to see about writing it because it was for me, joyous to write about her. And also, I was exploring what that process is like in exploring more about in depth what it was like to lose her. For myself, I think that for me, writing is always an explanation in the work and the joys in the edit. I write having no idea what I’m going to say. I kind of just sit there, you know, at the blank page and I throw a, uh, cast my brain out, my little rod in my brain and I see what pops up and then I follow it. And so, for me, writing is always exploration. I have no idea what I’m going to say. I maybe have an idea where I’m like, maybe I want to talk about, you know, what it was like to lose when mom said my name for the last time. But I have no idea what that is going to look like until I start to write it.

Steve Cuden: So, you have no intentionality going in as to what the outcome will be?

Cleo Childs: No, no idea. I go in and I say, I think I want to. Like, I wrote down a list of things I wanted to talk about, and I’d be like, this one seems to. I’m kind of drawn to this one. And so, I would just go, and I would wait and then I would. I usually hear first line in my head and then I just follow the line and then I go until I feel good, and I feel like it’s complete. And then I go see what I’ve written.

Steve Cuden: So, your poems, in a way, are a healing process for you?

Cleo Childs: Oh, absolutely.

Steve Cuden: Do you think that they are also healing for others?

Cleo Childs: That’s what I’ve been told in the beta reads. Everyone has told me, thank you. I mean, and that’s the thing is that, uh, if it comes out and everyone hates it, that is totally fine with me. Because someone told me in a beta read report, she said, I feel like you, you sat with me in my grief, and you held my hand. Done. Success. Everything else doesn’t matter. Someone else said, uh, you know, this person lost her younger brother. And she said, I felt seen and validated. Thank you for writing this. Another person said that they lost her, their mom, 20 years ago and they haven’t had these feelings before, but it felt like I validated their little girl that lost their mom. The hope was in releasing and creating it is that it would help it helped me in writing it. And it’s honest and it’s true as best that I could make it to my experience. And I hoped that it could help. The thing is that I have no idea if it would. That’s outside of my control. Right. I think that you put something out there with the hope that it will be meaningful to someone.

Steve Cuden: Of course.

Cleo Childs: And that’s what I’ve gotten feedback on, is that it is meaningful and that it’s helping. And I feel like I was talking to my, um, one of my friends earlier today, and I realized I came to the conclusion my mother was a helper and her legacy is helping. Because this book that is about us is helping, or at least it’s helped people that have read it up at this point.

Steve Cuden: So, I’m going to assume, and I think I already know the answer to this, but this is a cathartic experience for you. It was an emotional purging for you.

Cleo Childs: Oh, yeah. I laid myself a bare on the page. Uh, there’s nothing hidden. There’s nothing. And the thing that people keep saying is I appreciate how raw and honest it is. I think that when I came into it, I had this, uh. Not fear necessarily, but I thought that based off of what other people were saying is that it would be very scary to be vulnerable and to really something. Vulnerable.

Steve Cuden: Was it for me?

Cleo Childs: No. Because that’s how you get connection.

Steve Cuden: It requires a little bit of bravery, doesn’t it?

Cleo Childs: I don’t see it as being brave. I don’t see myself as being brave or courageous. I just see myself as being honest and, uh, authentic.

Steve Cuden: Okay. I think that’s probably accurate, but at the same time, not everybody could do what you’ve done.

Cleo Childs: I hope everyone would realize how much there is to gain by doing it.

Steve Cuden: That may be, but again, I think some people can’t get where you got to.

Cleo Childs: I guess so. I’ve never really thought of it that way.

Steve Cuden: I’ve written a lot of stuff in my life, and I don’t think I’ve ever come close to getting to there.

Cleo Childs: Oh, uh, well, it’s wonderfully freeing.

Steve Cuden: You know, I get in the zone, and I get to release. I definitely get there.

Cleo Childs: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: But the true emotional purging that you are definitely. It’s clear on the page and in the recordings. That’s very much coming from you and your soul.

Cleo Childs: Yes.

Steve Cuden: And it’s not made up. It’s not fantasy. It’s not science fiction. It’s none, uh. It’s not Ray Bradbury. It’s none of that.

Cleo Childs: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: It’s coming from you and your heart and soul. And I don’t think every writer gets there. Though I agree with you that most writers should if they can. But you do.

Cleo Childs: Yeah. I got very fortunate in something that one of my great mentors, Mary Gaucher, she became an editor for me very early on. She’s a Grammy, um, nominated songwriter. She’s insanely amazing. She’s incredibly talented. And I was looking at editors and the first time I had when we were going over this poem that I wrote, which is Don’t Cry for Me, I think it is. It’s the one where it’s from my mom’s perspective and initially I had for this martyrs S horror. Now I’m over here being like, I rhymed martyr and horror together. Because I’m from Georgia, I say horr. Apparently, there’s another way to say it, but my husband says horror. I don’t know, it just sounds so unnatural to me. So, I’m over here saying martyr and horror. And I’m like, that sounds great. And she goes, but is it true? Did your mother think of herself as a martyr? And I said no. And she goes, well, there’s your answer, you know. So, I had to delete my martyr horror. To my horror, I had to delete my great rhyme. But it was for the betterment of the piece. And so, she became an editor for me. And her sole job was to be a truth editor. We went over everything to make sure it was accurate and truthful, it was honest. And. And that was her. And she taught me how to be honest in writing. And then by being honest with myself and seeing how it connected to other people, that’s how I became able to do this kind of going to the prose and it’s in the book and expanding out the story in a very honest way and saying things that I think would be scary to other people. But to me, they led to moments of people not feeling alone. I think that there’s something in this idea that I felt so alone, like maybe I’m the only one who thinks like this.

Steve Cuden: No, you know that’s not true.

Cleo Childs: But I know that’s not true because other people opened themselves up to share their vulnerable side.

Steve Cuden: Sure, of course.

Cleo Childs: And it’s only through vulnerability that I believe that there’s connection.

Steve Cuden: You couldn’t make that connection if you weren’t saying things that were universal that other people feel. I don’t think you can make that connection.

Cleo Childs: I think too is that I was very fortunate that I started off writing a grief album because you cannot lie to people in grief. They have an impressive ability to know when there’s falsities.

Steve Cuden: That’s right. Did you set out to write an album? Was it the album was the goal?

Cleo Childs: No, no, no, no, no, no. I’m just saying that I’m very glad that I write about grief first, because I could not lie, and I knew that I couldn’t lie to people, and I didn’t want to lie to people, but I knew that they had, uh, uh, an insane ability because I had it to spot falsities if someone was being false with me and someone’s not being honest and true because I just knew it somehow in my soul, I knew that someone was lying to me or to themselves. And so, when I was writing, it was very important to me. And that’s why Mary is so valuable, is because she knew. She found my falsities and we purged them. We said, we have to delete those because she came through. And she’s like, nope, not. That’s not true. Or she would question me. She would say, is that true? It doesn’t feel true to me. She had an insane truth meter. And I would think about it, and inevitably Mary has 100% success rate. I would say, no, Mary, you’re right. I’m not being true with myself.

Steve Cuden: You were doing what William Faulkner once famously said, you’ve got to be willing to kill your darlings.

Cleo Childs: So, yes, martyr horror was one of my darlings. I was so pleased with martyr horror. And I had. It had to go, you know, and it’s by exploration and by going into the truth that I think that I learned more about myself. Like, for example, there is a poem that I wrote in grief where I was complaining about my husband. I adore my husband. I won the husband lottery. And he became to me, the most annoying person on the face of the earth when I was in grave.

Steve Cuden: Why was he annoying?

Cleo Childs: Because he was to my grief.

Steve Cuden: He wouldn’t let you grieve?

Cleo Childs: No, he was happy. Not happy, but he was just able to continue on with his life, right? And I am stuck and I’m like, my life ended. There’s no way that he can understand what it’s like to be in my body to lose my mother, right? And he would go in, I would say, close the door. So, I wanted to. Deep isolation. I talked to almost no one for like six months, right? And I’m an extrovert. I talked almost no one. I would wake up, go to work right, go to bed. So, my Husband’s wanting to interact with me because I’m his wife and he cares about me, and he’s. He’s concerned at this point. And I would have. My d. Had a door close policy, and he would open up the door, and I would yell at him, close the door. And m. I’m like, the door is closed. He’s like, are you okay? I’m like, that’s not the point. The door is closed. You just keep the door closed. Anyway, so I became incredibly frustrated with my husband. And I wrote in a poem, I said, the world is active, moving loud. And Mary, so smartly, she goes, it’s your husband, isn’t it? And I went, yeah, Mary. Yep, it’s. My husband is active, moving loud. It’s not the world. It’s this one person that’s active, moving loud. So, Mary was right. Mary is. She’s incredible. Highly recommend Mary Gaucher she as an editor because she will. She has an eye first spotting falsities like no one I’ve ever met. And through learning from her, I’ve learned how to be more honest with myself and more truthful. Uh, but Mary always gets a pass. Mary. Everything I do, Mary has to pass it because she will, you know, find areas where she’s like, that’s not Reese, you know. No, you’re not being truthful with yourself. And I will. Mary, you’ve done it again. Mary, you have found it. Mary’s insane. Mary’s wonderful.

Steve Cuden: Well, if you find someone like that, you hang on to them with everything you got. That’s a valuable person.

Cleo Childs: Oh, my gosh, is she? And I’ve learned how to develop it so that Mary, you know, doesn’t find things as much anymore. Right. But it’s important to have that person, particularly if you learn how to be honest and you’re wanting to be honest with other people, you have to be honest with yourself. And I’ve learned from her. So, I’m more honest with myself because of her truth editing.

Steve Cuden: Not every poet, certainly, and in fact, very few poets actually then go into a studio and verbalize their poetry and set it to music. Most poets don’t do that. They just put it on the page. And if they publish it, they do. What prompted you to go into the studio and record this? Was it because the producer and Nashville said you should? Is that the only reason? Or did it. Were you motivated in some other way?

Cleo Childs: Well, when the opportunity arises to go record an album, I was like, well, that sounds pretty neat.

Steve Cuden: So that came to you just like the poems come through you. This came to you?

Cleo Childs: It just came to me, like, this opportunity to go get an album. It never occurred to me. I never set off to do an album. Never occurred to me to even make anything I had public. The only reason I did is because I thought it might help people. And I was like, well, if someone’s willing to produce you, I guess you. You get produced. And then I thought, I think it can help people. And also, it sounds pretty neat. And I’ve never been to Nashville.

Steve Cuden: All good reasons.

Cleo Childs: Those are good reasons.

Steve Cuden: Where did the music come from?

Cleo Childs: We had a band come in. Or, uh, we had different session musicians come in.

Steve Cuden: But where did the music come from? Not the band, per se. I got that. But where did you get this music? Where did it come from?

Cleo Childs: Oh, they recorded it in the studio and prompted.

Steve Cuden: No. Who wrote it? Where did it come from?

Cleo Childs: Oh, it’s not written.

Steve Cuden: What do you mean it’s not written?

Cleo Childs: They just played it.

Steve Cuden: They just. It was just all improved.

Cleo Childs: It was completely improv.

Steve Cuden: Did they improv it while you were speaking or after you spoke?

Cleo Childs: That was just completely. I was in the studio. I was in the booth, and I would speak, and they would react to me, and I would listen to them, and I would react to them, and it was very organic. And we did everything in one or two takes, and then we were out and like, three hours.

Steve Cuden: Now, that’s fascinating to me because that’s not how most recording sessions go. There’s usually a process one way or another. Either the words are laid down in tracks and then the music’s laid down, or the music is laid down and then the voice is laid down. But you were doing it at one time.

Cleo Childs: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: And it was improvised at the same time. It was totally improv.

Cleo Childs: Yeah. That’s how I’ve done all the albums. So, I just find people. They maybe see the words beforehand, and then it’s. Except for one, Greta. Um, I wrote an album, and she is the only person on it, but on the other one, I had two people on it, and they would just. You know, they maybe were friends beforehand and. But they would go and just listen to each other and listen to me, and we would react to each other, and then we would be done.

Steve Cuden: Did you ever listen to anything back and then reject it?

Cleo Childs: If we ever need to go back, it was basically because I misspoke. And, uh, we needed to start from the beginning.

Steve Cuden: So, every piece of improv music that they gave you in the studio was completely perfect and acceptable to you then.

Cleo Childs: I was like, that’s great. W. You know, because it’s in the moment. I think that there’s this idea that I love is impermanence. Right. I love the idea that something is impermanent, and we caught something that cannot be recreated.

Steve Cuden: That’s true.

Cleo Childs: And I love that. I think the only thing I wish is I could be able to speak better because I’m from the south and I speak very quickly and so I stumble over my words and. But there were some, like magnolias. When I did my magnolias poem, I did that in one take.

Steve Cuden: Wow.

Cleo Childs: Other ones would go and be like, yeah, okay, that sounds pretty good. Next one. Then we’d go to the next one. We did everything chronologically and then we would just go run it through and that was it. It was done in one or two takes. If it was two takes, it was because of me. And then we were out in three hours.

Steve Cuden: That’s, uh, not only exciting to do, but you did it economically, which is even better.

Cleo Childs: Yes. We had the recording studio for the day, but I feel like it never occurred to me to do it, you know, any other way. Because when you feel like you got it and everyone else felt good about it too, and we’re like, we did a good thing, well then why do we need to go and get another one? I feel like that to me doesn’t make sense. If you feel really good about what you’ve done and we feel like we all did a good job, well, then you just go to the next one. You know, it wasn’t necessarily a matter of economics, it was a matter of did we get the thing, do we feel good about the thing and are we proud of it? Yes. Okay, next one.

Steve Cuden: So now clearly you did not go into any of this process as a means to.

Cleo Childs: No.

Steve Cuden: And I’m going to assume that at the moment you haven’t made a ton of money off of this. And that’s the nature of poetry period, that today there are very, very few poets that earn any kind of money from their work.

Cleo Childs: Mhm.

Steve Cuden: In fact, in the history of poetry, there aren’t very many. Though if you go back a hundred years plus, you can find poets that made livings off of their poetry. But today it’s much, much harder to do. That’s not in your intentionality, in any of this at this point.

Cleo Childs: No, no.

Steve Cuden: So, it’s not your profession, so to speak?

Cleo Childs: No.

Steve Cuden: It’s not how you earn a living.

Cleo Childs: I’m a marketer, I think too, is that there’s this Thing where I’THOUGHT about the idea between commercialism and patronages. Mmm.

Steve Cuden: Mhm.

Cleo Childs: My mother is my patron. I get to use my inheritance. So, I want to do. And I’m using it to create art and to be able to help people. So, I get to do what I want to do. And it’s important to me to carry on her legacy of helping. And the way that I can help is by what I believe is by putting out the story about my journey through grief. And it is helping. That’s the thing, is the beta re have told me, right. That it is helping, that they have been helped. And they’re thanking me as if to say, and that’s all I ever wanted, is to continue my mom’s legacy of helping. Right. I think that. And she is my patron, is my mother is my patron because she left me an inheritance. Where I have the ability and capacity to do so is to turn in, into help and to tell her story, um, and to tell my story with her. And I think because of that I don’t have this limitation, the self-limitation of making good art and things that I’m proud of, but I don’t necessarily have this limitation of saying what is commercially viable. And I think that for me, what I’m learning from these beta reads is that that’s actually something that is very valuable is the being free to create art for the sole reason of creating art that could connected to help. And it’s different, it’s a different way. But if you look at like the art that I’m really drawn to, I mean, Dylan did that, you know, Cohen did that. You do art for art’s sake, and you let the market come to you or it doesn’t come to you. But the point is, did you create art that moves you and it’s connected to people, and I’ve connected to these beta readers and for which case it’s successful. Right. And if there’s financial comes to it, that’s wonderful. But that’s not my intention.

Steve Cuden: I rarely bring up, you know, income sources on this show because that’s not what the show is about.

Cleo Childs: Right.

Steve Cuden: But I bring it up in this case because poetry in particular, and you correct me if I’m wrong, tends to be a pretty tough sell to make money off of.

Cleo Childs: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: And so, um, I’m. I’m saying that for the listeners, if anyone becomes inspired to do what you’re doing.

Cleo Childs: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: To also go into the world of poetry, to approach it like you are, as a means to make art, not as a Means to make money.

Cleo Childs: Yes, absolutely. I’m very, very, very fortunate that I have a patron.

Steve Cuden: Mhm.

Cleo Childs: And that’s my mother. You don’t have patrons nowadays?

Steve Cuden: You know, no, not, not really. I mean, there are kinds of patrons out there, but not the way we think of as patronage. So. Yeah, that’s a rough ride. Listen, being a writer in general, period, is a difficult way to earn a living. But poetry as a specific discipline is particularly difficult, particularly challenging. I’ve been having just a very, very fascinating conversation for, uh, just shy of an hour now with Cleo Childs. And we’re going to wind the show down a little bit and I’m wondering, are you able to share with us a story that’s either weird, quirky, offbeat stranger, maybe just plain funny?

Cleo Childs: Yeah. I’ll tell you my favorite story about my mom. It goes in the book, and I wrote it in because some of the readers were like, we want more stories about your mom. And I was like, well, okay, because this is my favorite one. So, my mother is the nicest, kindest, most gentle person you’ve ever met. You know, she is immensely thoughtful and very gentle and all this stuff, right? Imagine like, kind of like a fawn. Okay. I’m 13, my mom, she goes to the blockbuster and it’s Christmas Eve and she decides to get a funny movie for the 70s for us to watch. And so, she comes back, it’s Christmas Eve, we’re all in our jammies, you know, we have hot cocoa, and my mom puts in Blazing Saddles. Blazing Saddles cannot get made today. It is Mel Brooks in my opinion his Opus. So Blazing Saddle starts playing my sisters. I’m 13, my sister’s 9. Right? Blazing saddles for Christmas Eve. I’m like, mom, I’m loving it though. I am loving this. My sister gets bored, very lucky break for mom in the first 10 minutes and goes play the Sims in the ne, you know. But my mom horrified. She is horrified that she has brought this upon her family. I’m 13. Next year it’s Christmas Eve again. My mom goes back to the blockbuster, and she gets another funny movie from the 70s and it’s animal House.

Steve Cuden: She’s picking all the Christmas winners hor.

Cleo Childs: She’s horrified when she’s brought to her family two years in a row. And at the end of it she goes, I’m never getting another movie from this. Another funny movie from the 70s for us. Watch on Christmas. Which she never did. She did get me though, later on she got me Young Frankenstein and she got me, um. Oh, what is it with Mel Brooks? It’s the history of the world or something like that.

Steve Cuden: History of the World part one.

Cleo Childs: Part one, yeah. So, she got me those two. Luckily, those were not. I was a little bit older, and she didn’t give them to me for as a family movie night for me to watch when I was, uh, 13 and 14 at Christmas Eve. But she did introduce me to Young Frankenstein, um, and History of The World Part 1.

Steve Cuden: Well, out of sheer coincidence, one of the earliest guests I had on this show was Norman Steinberg, who was one of the co-writers of Blazing Saddles.

Cleo Childs: He’s my hero. I quoted a wed woes. How romantic. I quote it all the time. You know, we got to go back and get a bleep load of dimes. That’s what my husband says whenever he gets his wallet. We to go back and get a bleep load of times. I love Blazing Saddles. I love it. You know, Hedley, it’s Hedley Lamar.

Steve Cuden: You know, it is not PC anymore.

Cleo Childs: It is not. This thing could never. It could never get made again.

Steve Cuden: No, you couldn’t get that movie made today.

Cleo Childs: Holy. I’m surprised he even got made in the first place.

Steve Cuden: You know, it’s miraculous that they did get it made. And it’s a, uh, you know, it’s a classic, but it’s very much not PC today.

Cleo Childs: No. Mongo pawn, uh, was it Mongo is Pawn in life? You know, something like that. And it’s Candy Grant from Mango. I watched. I introduced my husband to Blazing Saddles as like a litmus test of if we could be able to get along together early on in our early dating career. I was like, do you like this movie? If not, I can’t date you. Like, it’s.

Steve Cuden: That’s the test.

Cleo Childs: That was my litmus test. It’s like, here’s. Blazing Saddles. Give me your thoughts. And this is a pass or fail test between if I could date you or not.

Steve Cuden: Well, that’s strict, but okay, I get it.

Cleo Childs: Like, if you don’t like Blazing Saddles, you’re not going toa like me.

Steve Cuden: All right, so last question for you today, Cleo. You have given us really, truly a ton of great advice all along through this whole show, but I’m wondering if you have a single solid piece of advice or a tip that you like to give to anyone who comes to you and says, how did you do this? Or if they’re just starting out in the business. Or maybe they’re in a little bit, they’ve done some writing or poems or whatever, and now they’re trying to figure out how to get to that next step.

Cleo Childs: Yeah. My advice is to break your own heart first. You have to care the most and you have to break your heart. You can’t expect other people to care if you don’t care. You can’t expect to move people if you don’t move yourself. So, I have cried over my manuscript. I mean, I cannot tell you how much I have cried over it. I broke my own heart. I mean, it broke my own heart to do it. And that’s why I think that it connects. You have to break your own heart first.

Steve Cuden: And do you think that in breaking your heart there’s the potential that you’re not able to get there, or do you have to work through it?

Cleo Childs: I would say you have to sit with it. I, uh, learned how to feel in grief. I don’t think feeling is a bad thing. I think sitting through. There’s no such thing in my head as good or bad emotions. They’re just emotions and they’re all valid.

Steve Cuden: Did grief ever stop you from moving forward? Even in that six-month period where you isolated yourself? Were you stopped at that point?

Cleo Childs: I stopped living. I never stopped feeling.

Steve Cuden: Did you write during that time?

Cleo Childs: Oh, that’s where I got all my stuff from.

Steve Cuden: I see.

Cleo Childs: That’s all I wrote. All I did was write. All I did was wake up, go to work, get mad at my husband, right, go to sleep. That’s all I did for six months. I completely isolated myself. I talked to no one. I did nothing. The only time I ever talked to someone was, uh. Uh. I started doing this radical thing too, where someone would say, how are you? And I was so apathetic. I would tell them. And I would use my poems as a methodology to tell them. Like one time I was in the Costco and, um, I wrote a poem, and I was like, eat a cookie, have a piece of pie. Your mother’s died. Nothing matters. Yeah. My friend Michael’s like, how are you doing? And I was like, here’s what I wrote today, Michael. And he’s like, so not well. And I’d be like, no, Michael, I’m not having a good time. My mom died, you know, And I feel like I started to use it as a tool to be able to feel. I felt things for the very first time. I think that I closed myself off from feeling particularly things that people are deemed as negative emotions and which is all I felt when I was in grief, but I also felt joy. I think that’s really interesting is I felt extremes for the first time in my life. I felt extreme despair, but I also felt extreme joy. And I think by unlocking myself to feel, I was able to feel all sides of the spectrum. And I think that when it comes to writing, feeling is not a bad thing. Feeling, I think, makes us human. And I think that opening yourself up to feel as you write allows other people to feel when they read. Writing is a technology. It allows people to communicate ideas, you know, emotions and thoughts into other people’s heads. And it is a diluted fashion. When you, when you write something down, someone receives it, it’s being diluted. But if you care so much and you feel so much when you’re writing it, then someone has to receive it on the other end, even in it diluted fashion. All this to say is to break your own heart first if you want to be able to move people and break their hearts.

Steve Cuden: I think that is, um, probably the most unusual bit of advice I’ve heard on this show. And I’ve been doing it a while. I’ve never heard anybody say that before, but it makes sense. Certainly, in your case it makes extra sense. As long as I think if you do break your own heart or your heart is broken, that you don’t go into a hole on it. Some people, uh, go into a hole.

Cleo Childs: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: You have to still live life.

Cleo Childs: Oh, absolutely. I think that you have to make sure that you’re doing it in a healthy way. Right.

Steve Cuden: That’s the key. Doing it healthy way.

Cleo Childs: But I think that point of the part is if you want someone to feel or to care, you have to care the most.

Steve Cuden: Well, that’s for sure. Uh, you’ve got to. If you can’t feel it, how can you express it?

Cleo Childs: How can you make someone else feel something?

Steve Cuden: Exactly.

Cleo Childs: If you don’t feel it first. And also take care of yourself. Right. I think that open yourself up, but only open yourself up to what you feel like you can take care of. But I think that if you want someone to feel, I think you have to feel it. If you want someone to resonate, has to resonate with you. First it starts with you and then it goes to someone else.

Steve Cuden: Well, I think that’s correct. It always starts with you. You’re the going all the way back to the beginning of this. You are the conduit.

Cleo Childs: Mhm.

Steve Cuden: You still have to be there in order for it to come through you. So that’s critical. That it starts with you.

Cleo Childs: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: So, Cleo Childs, this has just been a, uh, very, very interesting and a heartfelt conversation, and I greatly appreciate you sharing all this with us. And I certainly am delighted that you’ve been on the show. And I thank you for your time, your energy, and certainly for your wisdom in talking about how to write poetry, especially to work through your grief on. And I thank you.

Cleo Childs: You’re very welcome. I’m happy to be here. I love conversations, so I’m having a great day. Thank you.

Steve Cuden: And so, we’ve come to the end of today’s Story Beat. If you like this episode, won’t you please take a moment to give us a comment, rating, or review on whatever app or platform you’re listening to? Your support helps us bring more great Story Beat episodes to you. StoryBeat is available on all major podcast apps and platforms, including Apple Podcasts, YouTube, Spotify, iHeartRadio, Tune in, and many others. Until next time, I’m Steve Cuden, and may all your stories be unforgettable.

0 Comments