“I’ve always been somebody who believes that if something is calling to you creatively and it feels scary and or challenging, chances are that’s what you should be doing. So in those moments when I was daunted by where the story was going, I would encourage myself and say, don’t be afraid of it. Fear and action is a good thing. Just sit down and write it and see where it takes you.”

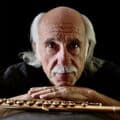

~Robert Monroe

Robert Monroe worked for more than a decade as a New York casting director and talent executive. His credits include projects with the Walt Disney Company, the John Houseman Theater, the Annual MDA Telethon, and the United Paramount Network.

Robert won a Clio Award for casting the Best Performance for Children for a Dole Pre-Cut Vegetables commercial.

Robert eventually moved to Portland, Maine to pursue a career as a photographer. Exhibitions of his work include the Biennial at the Portland Museum of Art, Photographing Maine: Ten Years Later at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, and Return to Peyton Place: Photographs by Robert Monroe at the Mohawk Valley Center for the Arts. And he’s a founding member of the Bakery Photographic Collective.

Recently, Robert published his debut novel, Bungalow Terrace. I’ve read Bungalow Terrace and can tell you it’s a beautifully written tale about four boys growing up to become a powerhouse rock ‘n roll group who endure all the breathtaking highs of success and harrowing challenges of the sex, drugs, and rock and roll fueled 50’s, 60’s, 70’s and beyond. Bungalow Terrace reads like an insider’s account of the lives of The Beatles, The Four Seasons, and The Beach Boys all rolled into one. I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book and highly recommend it to you.

WEBSITES:

ROBERT MONROE BOOKS:

IF YOU LIKED THIS EPISODE, YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY:

- Adam Rosenbaum, Author-Episode #336

- L.A. Starks, Author-Episode #334

- Hal Ackerman, Screenwriter-Novelist-UCLA Professor-Session 2-Episode #333

- R.J. Stewart, Producer, Xena: Warrior Princess-Episode #329

- Martin Dugard, Author-Episode #328

- Michael Buzzelli, Writer and Comedian-Episode #326

- John David Bethel, Novelist-Episode #316

- Joseph B. Atkins, Author and Teacher-Episode #311

- Max Kinnings, Novelist and Screenwriter-Episode #308

- Dr. William J. Carl, Greek Scholar-Novelist-Playwright-Episode #304

- Joey Hartstone, Screenwriter-Novelist-Episode #302

- Megan Woodward, Author-Episode #301

- Damyanti Biswas, Fiction Writer-Episode #281

- Hilary Sloane, Journalist-Documentary Photographer-Episode #236

- George Lange, Renowned Photographer-Episode #93

Steve Cuden: On today’s StoryBeat:

Robert Monroe: I’ve always been somebody who believes that if something is calling to you creatively and it feels scary and or challenging, chances are that’s what you should be doing. So in those moments when I was daunted by where the story was going, I would encourage myself and say, don’t be afraid of it. Fear and action is a good thing. Just sit down and write it and see where it takes you.

Announcer: This is StoryBeat with Steve Cuden A podcast for the creative mind. StoryBeat explores how masters of creativity develop and produce brilliant works that people. Everywhere love and admire. So join us, as we discover. How talented creators find success in the worlds of imagination and entertainment. Here now is your host, Steve Cuden.

Steve Cuden: Thanks for joining us on StoryBeat Beat. We’re coming to you from the Steel City, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. My guest today, Robert Monroe worked for more than a decade as a New York casting director and talent executive. His credits include projects with the Walt Disney Company, the John Houseman Theater, the annual MDA Telethon and the United Paramount Network. Robert won a Cleo Award for casting the best performance for children for a dull pre cut vegetables commercial. Robert eventually moved to Portland, Maine to pursue a career as a photographer. Exhibitions of his work include the Biennial at the Portland Museum of art, photographing Maine 10 years later at the center for Maine Contemporary Art, and returned to Peyton Place. Photographs by Robert Monroe at the Mohawk Valley center for the Arts, and he’s a founding member of the Bakery Photographic Collective. Recently, Robert published his debut novel, Bungalow Terrace. I’ve read Bungalow Terrace and can tell you it’s a beautifully written tale about four boys growing up to become a powerhouse rock and roll group who endure all the breathtaking highs of success and harrowing challenges of the sex, drugs and rock and roll fueled 50s, 60s, 70s and beyond. Bungalow Terrace reads like an insider’s account of the lives of the Beatles, the Four Seasons, and the Beach Boys all rolled into one. I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book and highly recommended it to you. So for all those reasons and many more, I’m truly delighted to welcome the brilliant writer Robert Monroe to StoryBeat be today. Robert, welcome to the show.

Robert Monroe: Thank you very much. I appreciate being here. Thank you for that introduction.

Steve Cuden: Well, it’s my great pleasure and it’s a delight to have you here. So let’s go back in time just a little bit. How old were you when you first thought about the entertainment industry and movies and stage? When did this start for you?

Robert Monroe: Well, I think the earliest memory I have of that was when I Was about maybe five or six or six or seven. I have three brothers, and one of my brothers and I, we used to put on, shows in the neighborhood. And, it was more than just sort of like, you know, make believe in the backyard. I mean, we would, sort of write the show, we would kind of produce it, direct it. We’d get all of the, neighborhood kids together to play the different parts. we made costumes, we made the scenery. And my brother, who was kind of like this Little U. P.T. barnum at the time, he would sort of go up and down the street knocking on all of the doors, insisting that people were going to come. So we had a big audience. And he would sort of dictate to all of the different mothers. O and you’re going to bring the brownies, and you’re going to bring the caramel corn, and you’re going to bring the candied apples. You know, because we needed refreshments during the intermission. So, in a sort of elementary way, we sort of recreating the old, Mickey Rooney, Judy Garland, let’s put on a show kind of film.

Steve Cuden: The Andy Hardy movies.

Robert Monroe: Yeah, exactly, exactly. That’s really the first memory I have of really, really knowing, on some level that I wanted to pursue at some point a career in show business.

Steve Cuden: Did you enjoy the idea of being a storyteller at that time?

Robert Monroe: Yes. Yes, because we would take. I mean, there were stories that we knew as kids, you know, fairy tales or, you know, things that we had read and sort of like, you know, the Little Golden Books. But we would sort of, you know, rewrite them to, sue what it was that we could or couldn’t do.

Steve Cuden: Sure.

Robert Monroe: And so, yeah, I mean, there was definitely an element of storytelling to it.

Steve Cuden: So you’ve obviously been a casting director and you’ve been a photographer and obviously now you’re a novelist. Do you think of the old careers that you’ve had or the other careers you’ve had, as in casting of photography, as also being a form of storytelling?

Robert Monroe: Well, absolutely. I mean, definitely photography. The one thing I will say is that I don’t think I would have been able to write the book if those other incarnations had not happened before them.

Steve Cuden: Why do you say that?

Robert Monroe: Well, each one really informed the next one. For example, as a casting director. Being a casting director taught me how to express myself.

Steve Cuden: Okay.

Robert Monroe: And it taught me, you know, how to sort of think outside of the box. And it allowed me the opportunity to sort of develop a personal, subjective style. It taught me the art of collaboration. It taught me diplomacy, and I think most importantly, it taught me to trust my instinct, while at the same time remaining somewhat objective and not taking things personally. Because one thing I since have learned is that when it comes to the arts, whatever that incarnation is, everybody has an opinion.

Steve Cuden: You think?

Robert Monroe: Yes. And not everybody is going to like your work, that’s for sure. Yeah. And so for me, you know, if you can just kind of get your ego out of the way and just sort of focus in on what’s in the best interest of what you’re doing, chances are it’ll be more successful.

Steve Cuden: Audiences, whether it’s one person who’s watching something or a thousand people watching something, can be very fickle.

Robert Monroe: Yes, exactly. Exactly. And then that sort of ideology of creating sort of this sort of subjective way of seeing certainly informed my photography because, you know, photography is all about how you see the world. I mean, how you. It is. You’re shooting through the lens. So my work as a casting director was essential in my work as a photographer. And what I sort of realized as I was using photography was that my work was somewhat conceptual. And basically all of my shows, which primarily, you know, they were about 25, 26 pieces in each show. They each had a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Steve Cuden: Interesting.

Robert Monroe: Yeah. And I was telling a StoryBeat through these pieces. I thought each individual photograph worked on its own as sort of, you know, a chapter can work on its own, or a certain scene in a film or a play can work on its own. But I always felt that. That the piece was strongest when it was seen together.

Steve Cuden: So they needed to have a sort of a theme that drew it together. Some kind of a StoryBeat of some sort that made it of a piece rather than a bunch of different individual pieces.

Robert Monroe: Yes, exactly. Exactly. And, I mean, I knew what the StoryBeat was and what I was trying to say. I, didn’t think necessarily it was that important that the audience knew necessarily, because they’re going to bring their own interpretation. You know, they’re going to filter it through their own experience anyway. But I definitely was trying to tell a StoryBeat I thought that each photograph informed the next image and then informed the next image. And I created sort of an arc until you get to the last image, which I thought was the end of the StoryBeat And without having done that with my photography, I don’t know if I would have been, able to write the book in the way that I did.

Steve Cuden: Okay. So it’s interesting to Me, because we’ll get to more detail on photography in a little bit. But it’s interesting to me that you did it that way because if you think about it the way you wrote Bungalow Terrace, you had lots of little individual things and scenes and characters that you drew out before they all started to really meld into one.

Robert Monroe: Right.

Steve Cuden: And the whole book is pieces of these characters lives that then becomes one whole.

Robert Monroe: Right, Exactly. And that’s really kind of. And I don’t know if initially with my photography, I, intended to do that, but I sort of realized that that was really the only way I found the photography interesting. M. You know, obviously I would see something and I would sort of be interested in shooting it, and I would shoot it, but I always knew that it was somehow connected to something else that would then tell a StoryBeat that would lead into something else.

Steve Cuden: All right, so at what point as you’you go from casting to photography and now you’re writer, when did you start thinking about being a writer, a serious writer?

Robert Monroe: Well, that’s sort of interesting in the sense that that came about somewhat serendipitously. I was still working as a photographer. I mean, as we know, you know, in every sort of creative business, you have highs, you have lows. And I was having a bit of a dry period. And, I was sort of questioning whether this is something I really wanted to continue doing. I was sort of questioning a lot of things that were going on in my life at the time. Because I was having a dry period of my photography. I started working at a restaurant on the weekends just to sort of bring in some extra money. And it was a Saturday night. I remember it distinctly. And I, had had a particularly difficult night at this restaurant. And I came home and I don’t even think I took my coat off. I sort of sat at the kitchen table. I do remember pouring myself a glass of Anazet, because that’s really all I had in the house.

Steve Cuden: Right.

Robert Monroe: And I needed something to drink. At that point I sat down at the kitchen table and I was really just sort of questioning every choice that I had made, every decision that I had made. What am I doing with my life? And literally out of nowhere, and I seriously mean this, the first line of the book popped into my head.

Steve Cuden: Wow.

Robert Monroe: The first line of the book is, they grew up on the same street. The street called Bungalow Terrace. Now, Bungalow Terrace was something that was a sort of a, flashback to my childhood. When, u. We were walking to school each day we would pass a street called Bungalow Terrace. And, you know, whenever we would pass it, I would always say out loud to one of my brothers, oh, Bungalow Terrace. That would make such a great title for a play or a movie or something, you know, Bungalow Terrace. The heartbreaks of Hollywood. My little, like seven or eight, like, dramatic way. And then obviously, I haven’t thought about Bungalow Terrorists in decades and decades and decades. And all of a sudden that’s what popped into my head. So it seemed somewhat secular. And I thought, well, you know, that actually would be a great way to start a book. But then I kind of just let it go. But as I tell most people with all great inspirations, it wouldn’t let me go. And before I knew it, the StoryBeat started formulating in my head.

Steve Cuden: And how old were you at this point?

Robert Monroe: I was, U. This was, about 10 years ago, so I was in my early to mid-50s.

Steve Cuden: So you didn’t start as a young writer. You weren’t a kid when you started to write. Did you get training as a writer anywhere?

Robert Monroe: I did not. I always knew that I had a capacity for writing. You know, even in high school and in college, I used to enjoy writing papers. And whenever I would get the paper back, the comments on the front of the paper would usually be, oh, very entertaining, you know, loved reading it. Kept me interested to the end, that sort of thing. And then obviously, in my other work, I needed to at least know how to wr professionally, like as a casting director would, correspondence, etc. And then with my photography, I certainly had to write, artist statements. You know, I certainly had to be able to write about my work, what I was doing and why I was doing it. and I would always enjoy that process. But I never studied writing. I never took a creative writing course. But what happened was, you know, this StoryBeat was sort of calling to me. And so what I decided to do is I said, you know, something. Just sit down and write something and see how you feel about it. So one night I sat down at the kitchen table again and I wrote a facsimile, of what is now the first chapter of the book.

Steve Cuden: Nice.

Robert Monroe: Yeah. And I honestly thought to myself, out of everything that I have ever done creatively, this was the most satisfying experience I had ever had. I just really loved the process of it, and I loved the creation of it and how I used my imagination, coming up with, you know, the few characters that were in the first chapter and that particular part of the StoryBeat And then I sent it to somebody that I trusted and I said, what do you think about this? And they really liked it. They were very honest. They said, I think the dialogue is a little melodramatic, but otherwise, I’m interested in the characters and I’d like to read on. I’d like to know what happened. And so I said, you know something? If you’re going to do this, then do it. But you have to be really, really disciplined about it. You can’t do it occasionally on the weekend. This now has to become your job. Right. So I, became very disciplined about it in terms of the research and in terms of writing every day, whether I wanted to or not, whether it was the weekend, whether it was the holiday, I would force myself, not force myself, because it’s something I wanted to do. Excuse me. But I would, commit to sitting and writing for four hours at least. If I wanted to do it longer, that’s great. But I had to do it at least four hours.

Steve Cuden: Going back just a half a step. When you were in business, in casting and photography, and you had to use writing as a skill set, mostly in a businessl like setting, not in a fictional setting.

Robert Monroe: Right.

Steve Cuden: And so your ability, I think that you’re just a naturally gifted writer than. Because your ability to tell a story through prose is excellent. And so there’s something that, you know, you just have it in you. And that does happen for people. And some people have to work at it and work at it and work at it to even get to the point where they’re even close to what your abilities are. Right. So you’re lucky in that way.

Robert Monroe: Well, thank you. I mean, I put a lot of effort and a lot of work into it. It was the most satisfying creative experience ever had writing the book, but it was also the most challenging.

Steve Cuden: Okay.

Robert Monroe: And it was also the one thing that I have done creatively that has really forced me to sort of go really, really, really deep and sort of peel away the onions in order to get to it to a point where I thought it was authentic and it was real and it would register and resonate with an audience.

Steve Cuden: So what were these challenges that you went through?

Robert Monroe: Well, first, you know, I wanted to write a book that spanned a long period of time. I wanted to be somewhat generational. And so Bungalow, Terrace spans 50 years.

Steve Cuden: Yes.

Robert Monroe: And, I knew that there was going to be a lot of research involved, but, I mean, that was something that I, for the most part, enjoyed. You know, researching the, music on, the recording industry in the 60s and 70s, etc. You know, I Had to research, the drug culture of the 60s. I had to research addiction, I had to read research, you know, aversion therapy, you know, particularly aversion therapy during the 1970s. There was a lot of material I really needed to research. And then once I felt like I was really confident in my research and I really knew what that was all about, then when I sat down to start writing, I just let all of that go because I felt confident that I could, draw from that. And I also took like huge, extensive. I mean I had a book about the size of an actual book of research. some of it made it into the book, some of it didn’t. But I thought it was essential and sort of me feeling confident that I could write about this material you need.

Steve Cuden: To do in a book like yours if you didn’t live through it yourself, which you didn’t, obviously you need to do something to familiarize yourself with the time and the types of people and what they were going through and what the tenor of the era was and all those things. And then the very specifics of the music industry and as you say, drug addiction and all these other things that were very. Not the way they are today.

Robert Monroe: Right.

Steve Cuden: Things are different today. So you would have needed to do a bunch of research.

Robert Monroe: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: And as you say, you absorbed as much of it as you could and you used a lot of it and some of it didn’t get in. And that’s the way it works.

Robert Monroe: Right, Exactly. Now. And I mean, obviously, you know, I grew up in that. I was a child during the 60s, I was teenager during the 70s, etc. So I mean, there were certainly decades that I lived to, because I was born in the late 50s. So I mean, I was certainly familiar with the decades and what was going on, you know, socially, etc, etc. But like I said, there was a lot of material that I really just wanted to make sure that when I put it into the book that it was authentic and that it was real to the time.

Steve Cuden: You weren’t in a. An all boy group in the 50s and 60s. So you would have had to have done a little bit of thinking about that.

Robert Monroe: Ye, exactly, exactly. And then the next thing that was challenging is that I have four main characters.

Steve Cuden: Yes, indeed.

Robert Monroe: I don’t just have one main character. And it was really important to me that each one of the characters get equal time, that it was balanced. And so what I did initially was I took each character as if I was writing a book just about that character. And I developed their story arc. And I sort of explored who they were and where they came from. And I created a backstory. And I did that individually for each one of the main characters, as well as Colin, who’s the somewhat secondary character, and Sheila, who was probably the main female character. I did that for those six people. And then once I sort of knew what each one of their parts was going to be, then, I sort of said, okay, now you have to figure out how you weave all of this together. And so, that was challenging, but it was really sort of exciting. And I realized that the way I was going to do that was making the group, the actual singing group, an actual fifth main character. So what would happen is I would write something about, say, the character of Vince, and then I would segue into a story about the group, which would then segue into, you know, sort of a chapter about, you know, Kevin’s experience. And I didn’t intentionally. I mean, I didn’t plot it out that way, but I sort of realized as I was writing it that this sort of fifth main character of the group is what was actually the glue that was sort of interweaving all the individual stories together.

Steve Cuden: Did you outline or did you just keep writing?

Robert Monroe: No, no, I definitely had an outline. When I say the big ticket items sort of made it into the book. I mean, I had certain highlights that, you know, I definitely wanted to include in the book, and they. Most of those made it into the book. But once I started writing the book, I sort of realized that I had to be more flexible with the outline because once you get to know your characters, once you begin to trust them, they will basically tell you where they want to go and what they want to do, and they will speak to you. I sort of realized that, you know, oh, I remember I was writing the chapter, where they are in, Malibu, California. And the whole purpose of that chapter in the outline was for the character of Vince to have his first LSD experience and for the character of Kevin to have his first gay sexual experience. And there was a character in the chapter, a character called Jessica Lyon, actress, who is just supposed to appear in that chapter. But then as I was writing the chapter, I sort of realized that Jessica and Steve wanted to get married. And I’d never thought about that. Steve was supposed to get married, but, you know, later on, deeper into the book, he was never supposed to marry Jessica. She was just, supposed to appear in that one chapter. But it became very clear to me that that’s what these two characters wanted to do, which would significantly change the character of Steve’s, you know, the trajectory of his story.

Steve Cuden: Right.

Robert Monroe: But I thought, this is really, really interesting, and it was really exciting to me. And I had that experience throughout the book. And it sort of changed the outline of the book because, you know, how somebody got from point A to point B. I thought they were going to take the highway, and they end up taking the back roads. And I just sort of had to just trust my instincts and trust what the characters were sort of guiding me to do, to know that this was the right way to go.

Steve Cuden: Well, that’s the beauty part of being a writer, is that you can do that. You’re the God of the story and as you’re going along, you can make those changes. Because unless somebody is paying you to write it and expecting a certain outcome, you can go in whatever direction you want.

Robert Monroe: Right? Exactly. Exactly. And that’s what was wonderful about it. And then, you know, obviously, I had to find my particular voice, what I was trying to say. But then I sort of realized very early on it’s not necessarily all about that. What it’s about is, like, finding the character’s voice and how that particular character would express what you’re trying to say. And so it was very important to me to create a specific voice for each of these characters.

Steve Cuden: Sure.

Robert Monroe: There’s a chapter that Takees plays at a club called the Cornet Club. 90% of that chapter is dialogue. And I wanted to make sure that, like, the, reader knew exactly who was talking when. And I didn’t want to rely on. Said, you know, Vi, said David. And so I really had to find their voices.

Steve Cuden: Do you think that that came from your years as a casting director, that you understood how those distinctions would be?

Robert Monroe: I think that was helpful. And I also, found each one of their voices. It was interesting. Before I became a casting director, I had initially briefly thought about being a performer, and I studied acting. and I’d gone to college, and I was a theater major, etc. So I actually went back to my acting training. And what I would do is I was sort of. Because I didn’t think that it was going to ring true or authentic. And it wasn’t going to resonate unless I was in the same emotional place that the character was at that particular time in the story But I said, well, I think what would work for me as a writer is to get myself to sort of substitute something in my own life that evoke the same emotion, get into that Same emotional place, and then write it. So I started doing a lot of sort of sense memory work, you know, which is part of the Actors studio et ceter, etc. Which is. Was very popular back when I was sort of studying acting. Right. And I set myself into that emotional place and then I would write it and then the voice would come to me. Because I sort of realized into the work that even though initially I thought, well, I know all of these characters, you know, I grew up with some of these boys. And, you know, I’m from a big Italian family, so I know who Vince is. And I certainly work with men and women in show business who are like Colin, controlling. But I sort of realized that, you know, basically all of the characters are just different aspects of me, which I think everybody discovers.

Steve Cuden: I think most writers will tell you that that’s exactly what it winds up being. Even if you’re writing a superhero or you’re writing, some strange otherworldly character, it’s still going to reflect you in some way.

Robert Monroe: Right, exactly. And the way that I found that voice was by getting in touch with that part of myself. And sometimes that was complicated and difficult simply because some of the characters are doing things that are not necessarily the most commendable or admirable, of course. And I still had to get in touch with that part of myself in order to create that part of the story

Steve Cuden: Well, that’s what makes this story so compelling, Robert, is that, it’s filled with this frictional thing that we call conflict. And without that, you don’t have much of a StoryBeat that’s interesting to read or watch. And so you have that all throughout it because of these characters and their flaws.

Robert Monroe: Right. And that was really important to me that these characters be human. I really didn’t want to have any specific heroes, any specific villains. And that’s what creating all the back backstories. And a lot of the information from the backstories made it into the book. But I wanted the reader to be clear that if somebody was doing something, there was a very specific reason as to why they were doing it. You know, they could trace it back to their upbringing, they could trace it back to their socioeconomic background. They could trace it back to their experience. You know, so that when somebody who. That you have fallen in love with as a character now does something that you don’t necessarily like, you don’t lose heart because you understand why they made that choice. And that was really important to me that each of the characters beloved in spite of their humanity or because of their humanity, I guess I should say.

Steve Cuden: So you obviously, we’ve talked about it. You did a lot of research on this.

Robert Monroe: Yeah.

Steve Cuden: In the very, very beginning, you had no characters at all. You didn’t know who you were going to write about. You didn’t have a story all you have was that first line of the first chapter. So you didn’t know what was gonna happen. And you were in that process of discovery which all writers go through. Did you sit down and develop, each of the characters separately in their own little folio or whatever it would have been, or did you just sort of keep going and build and build and build as you wrote?

Robert Monroe: I think I just kept writing and built and built and built as I went.

Steve Cuden: Well that’s a perfectly viable way to do it.

Robert Monroe: Yeah, I didn’t, I didn’t create like this, a folio for each individual character. I certainly was keeping track of what they were doing and where they were going, you know, to make sure that it made sense. because there’s a lot of details and I didn’t want some detail to sort of slip through the cracks. And then all of a sudden, you know, I’m in a particular chapter and I’d forgotten that, you know, this had happened like five chapters beforehand. So I mean, I was, I was very meticulous about making sure that everything in each chapter made sense based on what they’d come before.

Steve Cuden: Right.

Robert Monroe: But yeah, I just, I just kept, you know, sort of writing and building.

Steve Cuden: Do you think that you could have written this when you were in your 20s, or do you think you needed to be a little more mature in life to have written it?

Robert Monroe: Oh, I could never have written this in my twenties.

Steve Cuden: You could not?

Robert Monroe: No. I didn’t have the life experience nor would I have had the capability to go sort of deep within my own emotional life to access that material. I didn’t have that kind of self awareness at that time to write this kind of a story You know, I could have written something maybe more on the surface that, you know, maybe there were similar plot points, but I never could have written this in my 20s now.

Steve Cuden: Well, of course you absolutely could have devised a story of some kind that would have been in a similar m place. But the, as you say, the depth of this, I don’t think you could have. And I think that this is true. I’m saying that for the listeners who are younger to understand that it’s okay to keep writing, you need to keep writing, but you need to also sometimes get a little bit more life under your belt.

Robert Monroe: Right. Exactly. Exactly. And, I think I needed to be the age that I was. I think it was the perfect time for me to write this book. I think it was the right time in terms of my own emotional growth to write the book. I think I had enough experience in order to access what I needed to access to really write these characters in a really true and, whole way.

Steve Cuden: So I’m always fascinated by story tone. I’m interested in it when I’m watching a movie or TV show. I’m certainly interested when I’m reading a book. Some authors are really good at setting tone. I think you’re one of those. I think you’re really good at setting a tone within the StoryBeat Were you conscious of that? Of the tone of the story?

Robert Monroe: I wasn’t necessarily conscious of the tone. I mean, I knew that I. I mean, as a writer and also as a photographer, I’ve always been intrigued by the shadow side of the human experience. So it was sort of this conflict or this crisis of self that I was sort of exploring in the book. But at the same time, I don’t think you could really have a story with some darkness in it without sort of going back into the light.

Steve Cuden: Sure.

Robert Monroe: You know, I. At least for me, I mean, that’s the kind of story that I like to read. so to me, that was just sort of half the story Sort of, the shadow that exists in the human condition and in society. the other side of it is, you know, what happens to an individual when they are sort of exposed to the miracle of a shifted perception. I sort of equated it with, like, you know, sort of like getting Dorothy into the witch castle and then ending the movie. To me, it’s like, no, you have to get home. So for me, going into the woods, you know, to quote Stephen Sondheim, to get them into the woods is the first part of the StoryBeat But then to me, the exciting part, the revelation, is how they get out of the voices.

Steve Cuden: Oh, sure.

Robert Monroe: So I think maybe peripherally, I was, aware of tone, in terms.

Steve Cuden: Of that there’s certainly a bunch of darkness in this story but you also have a lot of light, too.

Robert Monroe: Yeah, well, that was the whole point of the book, I think. You know, I really wanted to sort of write about, you know, forgiveness and reclaiming one’s life. You know, it has a lot to do with redemption and sort of shift in perception and seeing yourself in the world in a different way. And I think those themes, at least for me, sort of lent to a specific tone. But, you know, I mean, I knew when I was writing the darker parts of the book, I said, you know, don’t be afraid of this. I’ve always been somebody who believed that if something is calling to you creatively and it feels scary and. Or challenging, chances are that’s what you should be doing.

Steve Cuden: Yeah, very good.

Robert Monroe: Yeah. So in those moments when I was somewhat daunted by where the story was going, you know, I would encourage myself and said, don’t be afraid of it, you know, and if you are afraid of it, fear and action is a good thing. I said, but just sit down and write it and see where it takes you, you know? And the way to do that was I had to find that place in myself that have the courage to sit down and explore those darker parts of the book.

Steve Cuden: I think it’s excellent that you’re pointing out that you had to go into the story like the characters are going through their own challenge, their own quest. The quest for you was the book itself. Writing the book.

Robert Monroe: Yes, exactly. Exactly. You know, and it was very therapeutic for me, God knows. I mean, there was one specific part of the book that I resisted writing for a long period of time. It has to do with the character of Melissa. I don’t really want to give anything away, but it has to do with the character of Melissa. I was very reticent to write that it was inspired by an incident that happened in my grandmother’s neighborhood. O It didn’t come strictly from my imagination, but I remember as a child, I was told this particular story and it kind of haunted me most of my life. And as I was writing the book, I sort of realized that everything that was happening in the character of Sheila’s storyline was leading up to this. And I was resisting it and resisting it and resisting it. And, you know, I was convincing myself that I couldn’t write it. I didn’t. I wasn’t talented enough. I couldn’t write it in a responsible way. I just didn’t want to deal with this particular issue. And then one day I said, you need to just get out of your own way. And once again, I repeated that statement. Fear and action is a good thing. I mean, fear that keeps you immobilized is not. But, you know, if you’re doing something, if you put yourself into an active place, it’s okay if you’re feeling a little, you know, overwhelmed or a little fearful about it. And I just sat down And I wrote it. It’s one of the proudest moments of my life. Not only as a writer, it as an individual. I wrote it, and I’m really proud of how I wrote it. And not only did it sort of really worked with the story and I thought it was very cathartic, but that story that I’ve been haunted by since childhood no longer haunts me.

Steve Cuden: That’s really great. it was a form of catharsis for you to write that chapter, that story So from your inception of it, sitting at the table with the glass of, alcohol, and to the completion of it, how long did it take?

Robert Monroe: It took from that moment, including all the reason it took five years for me to write the book.

Steve Cuden: Five years.

Robert Monroe: Five years, yes.

Steve Cuden: How long did the first draft of it take till you got to a draft?

Robert Monroe: Oh, yes. The first I wrote about. I think I wrote five complete drafts of the book. It was important to me to write different drafts, within that structure. I also would go back and tweak things as well. So it was sort of a combination of both. I did just write draft and then go back and rel look at it. I would write and then I would tweak. And then when I thought I tweaked enough or I didn’t have any more objectivity about it, then I would move on. but I would say the first draft took me the longest, so I would say probably at least a couple of years. And then the additional drafts took a shorter period of time. the last drute being primarily just cutting all the excess out of it, sort of editing it down and just really tweaking the dialogue so that the dialogue worked for me. I mean, I must say that the hardest part of writing this book was writing the dialogue. I have such enormous respect for screenwriters. Teleay writers, playwrights, you know, because they’re dealing just strictly with dialogue, and dialogue is hard.

Steve Cuden: Well, playwrights are dealing. Most playwrights are dealing mainly with dialogue. Most screenwriters should be dealing with visuals.

Robert Monroe: Right, right.

Steve Cuden: That’s what should be going on because. And dialogue. And actually, truly great cinema. Truly great cinema has very little dialogue.

Robert Monroe: Well, that’s true. That’s very, very true. There’s still a medium that requires dialogue and, you know, tremend respect.

Steve Cuden: Oh, no question. Do you definitely need to be able to write dialogue as a screenwriter? But it’s different than a playwright. That’s generally writing a play with dialogue mainly.

Robert Monroe: Right, right. Exactly.

Steve Cuden: So as you were writing your fourth and fifth draft, so you were deep into the process at that point, how challenging was it for you to overcome things that you weren’t certain about or you had a lack of confidence about, assuming you did?

Robert Monroe: well, I did. I did. The best way that I did it is sometimes I had to give myself a little distance, you know, because I’d be reading certain things that now I think are wonderful. And I would say to myself, is this boring? Is this. I mean, you know, and I think it’s because I was so close to it. Sure. And I said, you know, at a certain point, you need to get some objectivity about it. So, I mean, at that point, I would sometimes go away from it for like, a couple of days, sometimes a couple of weeks, and then I would come back to it with some fresh eyes. I just needed to get some objectivity about it.

Steve Cuden: We call that artistic distance.

Robert Monroe: Right? Yes. So I needed to do that. And at some point, I had to discern whether or not instinctually I thought, this isn’t working. You know, I was listening to my intuition or if I was coming from this egoic place, because your ego inevitably will take you to a place of resistance. And, being in the place of having to feel you need to defend something. And I said, I need to discern. You know, am I having issues with this? Because intuitively I know that it needs work, or it doesn’t belong in the book, or, it’s not. I need to tweak it a little bit more. Or is this just me and my own personal insecurity getting in the way?

Steve Cuden: Of course. Well, it’s very hard when you’re locked in a room by yourself for four or five years and no one else is really sitting over your shoulder telling you, yeah, that works. And, no, that doesn’t work. You’re doing that on your own. It can be really challenging to feel confident about it.

Robert Monroe: Yes, exactly.

Steve Cuden: Did you know, though, as you were writing that the book was working on some level?

Robert Monroe: Yes, I did. And, the way that I did that was that if even after having written something and sort of living with it for a long period of time, if I read again and I still had some sort of emotional response to it, then I knew that it was working. There’s this one chapter where there’s a significant breakup of a relationship. And whenever I read that chapter, at the end of the chapter, I felt something and I said, you know something, this is working. Because I’ve read this a million times and I’m still feeling something.

Steve Cuden: Oh, it’s worse than that. You were. Didn’t just reading it a million times. You wrote it.

Robert Monroe: Right? Exactly. And, that was kind of my litmus test was if I read something and I was still challenged by it, or I still found, that it had a certain amount of tension or conflict, or I had some sort of. Had. If I had some sort of visceral response to whatever it was, then I knew that it was working.

Steve Cuden: That gives you a sense of confidence. Now, did you then at some point give it to confidential friends, or did you give it to an editor? Or what did you do with it once you thought it would needed some feedback?

Robert Monroe: I gave it to some people that I really trusted. a couple of them were more acquaintances, but there were people who, you know, there were a couple of academics that I gave it to. I gave it to an English teacher, and I gave it to a variety of different people in different age groups. Like, I remember I made a point of giving it to a young woman in her 20s, because there’s certain things within the book that deal with young women and the issues of consent. And I really wanted her feedback in terms of that. And then I gave it to another individual who was actually in their 70s. And I gave it to another individual who was sort of more in their 40s or 50s.

Robert Monroe: I gave it to both men and women. I gave it to a larger demographic just to see what the response was. And, the response was very, very positive. And they all wanted to talk about it. And, you know, I would invite them over and we would sit for a couple of hours and we would just talk about what they felt and what the response to the book was. And I was really, really open to their comments and their criticism. I guess the question I would always ask myself, and I did this in the editing process of the book, the only question I ever asked myself is what this individual is saying or what they’re proposing. Does it make it a stronger book? Does it make it a stronger piece? If the answer to that question was yes, then I was like, great, let’s do it and move on. If the answer was no, then of course I would stand up for what I believed, you know, and I would fight for what I wanted in terms of something. But I would have to say, particularly in the editing process, that at least 95% of the time, what they suggested made it a stronger book. And so I just said yes. And once again, you know, it’s one of those questions of getting your ego out of the way and just asking that one question. And so that became Sort of my mantra during the editing process is what the propose doesn’t make it a better book. And if the answer was yet, I didn’t have a discussion about, I was like, okay, we’ll do that.

Steve Cuden: I think that this book would make an excellent movie. Do you have any thoughts about taking it down that road, trying to get someone interested in that?

Robert Monroe: Absolutely. I think it would make a great movie as well. Or a limited series, that kind of thing.

Steve Cuden: Or a limited series. Sure.

Robert Monroe: I definitely would love that to happen. I’ve even considered challenging myself to write a screenplay for it.

Steve Cuden: Well, you probably would be doing yourself a favor if you at least tried. But part of the problem. I will tell you from years and years and years of being in the screenwriting business that most people who write novels are not very good at them, adapting them into screenplays. A screenwriter who would adapt your work would not have an attachment to it. Your attachment to it means that you’re not going to want to give up certain aspects of it that you may have to do when adapting it to a screenplay. That’s a subject for a whole different day. But I still would encourage you to try to do that. Just to have that experience, knowing that it may work and it may not. And that’s, you know, that’s going toa be up to others to judge for you. I’m curious, did you work with an editor before you published it?

Robert Monroe: I worked with it. I mean, I worked with a copy editor before I published it.

Steve Cuden: That’s what I mean. A copy editor.

Robert Monroe: Yeah. Yeah. Ye. Yeah, yeah. Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. I worked with a copy editor. Yes. And she was lovely, and she was wonderful. And, u. There were certainly times when she challenged me. I remember, she had deconstructed and reconstructed this one particular paragraph that I thought was initially brilliantly written. But once again, I said, you have to get that out of your head. Just look at what she’s done. And the interesting thing about it is that I think, writing has a particular rhythm to it. Sure. My writing has a particular rhythm to it. And I had that rhythm in my head. She’s now turned it into 3, 4. You were writing a poker. She wrote a walls. Which is better. Is it better as a waltzer? As a poker. And so when I got the rhythm I had written out of my head and just read what she put down, how she reconstructed it. I mean, she didn’t change any of my words. She didn’t change the meaning. She didn’t change anything. She just changed a lot of the punctuation. And she changed some of the structure of it. And when I sort of could just sort of see it from that standpoint, I said, you know something, I think what she did is better. And so I left it alone.

Steve Cuden: I find it interesting that you compared the rhythm. Well, rhythm is a musical thing, but you wrote a book about musicians and music in the industry and you compared it to a polka or. What did you say? A polka or a, or a waltz. Very, very good. But I would be remiss, as we’re heading toward the latter part of the show, I’d be remiss if I didn’t talk to you for a moment about your photography. We talked about it very briefly at the beginning of the show. But I’m curious, what is it about photography that’s spoke to you that led you from going from New York up to Portland, Maine to become a photographer? What does it say to you?

Robert Monroe: Well, I had always been something of an amateur photographer and being a casting director, at least at that time, you know, people would come in and we would put everybody on videotape. So I was working with the visual image. Sure, it was a moving image, but it was visual. And I even remember at the time playing around instead of just putting it on a static camera and, just, you know, sort of documenting the audition. I would start playing around with the camera. You know, I’d go in for more of a close up. And I really found working with the image very interesting. And then when I decided to leave show business, and I knew it was time to leave, so I had no regrets whatsoever. I said, well, you know, creatively you need to start focusing on something. I said, well, you’ve always been a bit of an amateur photographer. Why don’t you just start studying it? You know, not professionally, but so I studying it more seriously. So I studied privately with a photographer and I took him classes at the New York center for for Photography. And then I took a trip to Ireland. And I took a trip to Ireland with the New York center for Photography with a bunch of other photographers. And when I was in Ireland, once again, like when I was writing the book, I literally got lost in taking these photographs. I mean, I literally just would immerse myself. And it was interesting because the, quote unquote professional photographer who was with us at the time said, you know, it’s interesting you can find anything interesting to photograph. You just constantly photographing things. Everybody else is like looking for something interesting. You just photograph something and find something interesting about Anything. And that’s when I came back and I said, you know, I think this is what I really want to do.

Steve Cuden: Okay, so what from your perspective makes a great image, great?

Robert Monroe: Oh, I think it’s very subjective. I mean, for me, when I first started, because I went back to graduate school, I didn’t finish graduate school. But what brought me to main was that I decided to go back to graduate school for photography. When I got there, the woman who was my advisor, obviously, they looked at my portfolio and they accepted my work. But the one thing that she said to me is, she said, your composition is classic. It’s like textbook classical composition. It’s just beautiful. It’s stunning. But where’s the tension? There’s no tension in your photographs. And that’s all she said. And so I then spent a good deal of time trying to create tension in my work. How do I do that? And I sort of figure that out for myself. And I think that’s a very personal thing. I mean, I was really not really interested in taking. And I think there’s, you know, the decorative arts are a beautiful thing. My house is full of decorative art. I just went, not really interested in doing that. You know, taking photographs that necessarily want to hang over your couch. And like I say, I respect people to do that. It just didn’t interest me. And so for me, with a great photograph is the great photograph that tells a story that has tension, that allows me as the viewer to filter my own experience through myself and then to come up with some sort of interpretation about what I’m seeing. If the, great photograph to me is a photograph that elicits some sort of emotional response, and if a photograph elicits an emotional response, then on some level, whatever that response may be, I think it’s very successful.

Steve Cuden: Well, that’s true for your writing as well, isn’t it?

Robert Monroe: Yes, exactly. And I think that’s why my photography informed my writing because, you know, that’s what I was always looking to do. I remember I went to see this retrospective on the, photographer Walker Evans. And, you know, I was like an emotional rack by the time I got out of there. These. His. I mean, his images are so stunning. I mean, technically, they’re just visually beautiful, but at the same time, each one evokes a different, more deeper emotional response based on what he’s shooting. And u. It was one of those thrilling exhibitions I’ve ever seen in my life.

Steve Cuden: Were you known for a specific kind of image? Was it buildings or.

Robert Monroe: Yeah, I primarily shot at night. and that came from a challenge I was afraid to do because I was challenged to do that. I did it because I, I always wanted to be in control of the light. I want the light to be balanced and even because I could control the image. And so, when I was challenged not to do that, I said the only way I could do that is to go out shoot at night. Because you can’t control. There is no light at night. Itep maybe a street lamp or, you know, maybe some u storefronts and the moon. So you can’t control that. So if you can become comfortable in that scenario, it’ll really enhance what it is you’re doing. So I did a lot of night photography and I also did a lot of architecture, but primarily architecture from the 18th and 19th century. Sort of this decaying facade, as it were. And I would shoot it at night because the symbol for the soul is the house. And so, I found this very interesting. These sort of, these one sort of glorious, magnificent structures that were now somehow in decay, they were somehow in ruin. They spoke to me in terms of, the human experience and the human condition and what sometimes happens in our lives when we don’t address what it is that we’re being asked to address. You know, we sort of become these sort of decayed houses. So, yeah, so I primarily took a lot. So I was known for that sort of darker image of, night shooting and that architecture.

Steve Cuden: You’re into negative space as well.

Robert Monroe: Oh, yes, yes, yes, exactly. Yeah.

Steve Cuden: Because that’s. If you’re shooting at night, you’re going to have a lot of dark, or black even.

Robert Monroe: And then the challenge was how to create that balance of light with that kind of a negative.

Steve Cuden: And also when you’re shooting like that, I imagine that your, the viewer’s focus will be probably drawn to where the light is.

Robert Monroe: Yes, for the most part. But like I said, I mean. And the one thing I declare is that, I’ve never shot digitally ever. I only shoot on film. I only still shoot on film. So I haven’t shotow time. So all of that balance of that dark, that negative light, or that the absence of light, all of that balance has to be manipulated in the dark room, which is trickier than obviously doing it in Photoshop.

Steve Cuden: A lot trickier.

Robert Monroe: For example, I did, one of the shows that I did, and one of the reviews, the gentleman said that, you know, it was all shot on film. They were silver geelloped in prints. So if there were like, you know, Phone lines in front of the building. I had to somehow deal with those phone lines and make it work as opposed to going into Photoshop, and eliminating phone lines. So. But that was part of the exciting part for me to have these challenges in the field and figure out how I’m going to make this work in the Darkro room, so that it’s, you know, sort of, a, seamless, sort of graceful piece. I never liked when somebody immediately went directly to something in the photograph. I really wanted them to really look into the photograph. I wanted to them to discover something within the photograph. And so the way that you do that is you don’t give anything specifically, you know, all of that light or all of that focus, and then they sort of discover it on their own. Once again, I wanted them to. To interpret the story from the photograph. And the only way to get them to interpret the story on the photograph is to have to look at all of the different chapters in the image.

Steve Cuden: Once again, I don’t want to harp on this, but, yes, you then really took that and used it in the book because it’s. What does the reader get by going deeper into the story?

Robert Monroe: Right, Exactly.

Steve Cuden: Well, that’s great. I’ve been having just a fantastic, fun conversation for almost an hour now with Robert Monroe, who’s published his first book called Bungalow Terrace, which I do urge you to check out. And we’re going to wind the show down just a little bit.

Robert Monroe: Ah.

Steve Cuden: At this point. And I’m just wondering, in all these experiences you’ve had, whether in casting or photography or in writing your book, can you share with us a story that’s either weird, quirky, off feet, strange, or maybe just plain funny?

Robert Monroe: Yeah. I don’t know how quirky or offbeat it is, but, it’s something that, made a significant impact on me.

Steve Cuden: Sure.

Robert Monroe: as we talked about in the, 80s, I was a casting director, and at the time I was casting television commercials. And it was Sunday night and I was watching the Tony Awards, and this actress that I knew professionally won the Tony Award for best actress in the play, which, as we all know, is, you know, a hugely significant feat and a great honor. And of course I was thrilled, you know, for her. And then the next day I came into my office and I had a casting session. I was casting a commercial. And the first person who walked into my session was this actor. And I was actually stunned. And I remember I looked at her and I said, what are you doing here? And she looked at me and I Said, you just won the Tony Award for best actress in a play. Because in my judgmental mind, this, audition for this commercial was now somehow beneath her. And she looked at me, and I’ll never forget. I mean, I can still see her face and with such stillness of presence and with such humility. She looked at me and she said, yes. She said winning the Tony Award was wonderful. But then I woke up this morning, life goes on. And she told me she had laundry to do and she told me she had to get her kids off to school and that she had to get ready for this audition because she wanted this job. And that was a really teachable moment for me because first and foremost, it made me realize that it’s the caliber of this kind of performer that wins Tony awards because they’re about the work. They’re not about, you know, all the accessories that may or may not come with the work. And second, it taught me that when it comes to work, there is no pecking order. There’s no hierarchy of work. There is no, this is good work, this is bad work. Work is work. It’s what you bring to the work that’s important. That’s something I’ve tried to carry through most of my life. So I thank this actress tremendously for.

Steve Cuden: Teaching me that is a really good teachable story And just as importantly, she’s a working actress and she needs the income. It’s part of the process. She. And by the way, people in the theater tend not to become rich unless they somehow find their way into TV or film. And even then they might not become rich. But she was clearly saying to you and to herself, no doubt, this is a job. I need the work. I’m go going toa do this at the best of my level. I don’t look down. It’s just another job.

Robert Monroe: Exactly. And it was my own judgment of it. I was the one who created that judgment about, like, of course, just won a Tony Award. Why would she want to audition for this commercial? You know, she’s too good for this. And she was like, no, why are you slumming here?

Steve Cuden: You know?

Robert Monroe: Exactly.

Steve Cuden: No, it’s a job. You know that we’re all working stiffs to a certain extent, and very few people get to that level where they have so much income and so much going on that they don’t have to think about looking for other jobs. But most people in the business, even awardurnners. And by the way, I find it interesting about the Tonys’the Emmys, the Oscars, et cetera. That is the only one and only place, really, other than maybe premieres or opening nights, where the quote unquote glitz and glamour of show business exists. Everything else is just normal offices and dirty, sound stages. And it’s not glitzy and glamorous at all.

Robert Monroe: Right, Right. Exactly. Exact. Exactly.

Steve Cuden: So, last question for you today, Robert. You’ve already shared with us a pretty significant amount of advice throughout this show, but I’m wondering if you have a single solid piece of advice or a tip that you like to give to those who are starting out in the business, or maybe they’re in a little bit trying to get to that next level.

Robert Monroe: Yeah, I mean, it’s the advice I try and take myself, that no matter what it is you were doing creatively, try to do it with enthusiasm. Try to bring to it a certain amount of curiosity. try to do it with a certain amount of excitement. Because when you, sort of infuse the work with that kind of passion, only something positive can come from it. You know, I’m a firm believer in that. and that includes work that you may not initially be that excited about. For example, say you received a commission or you’ve decided, like, we all have, I’m going to do this job for the money. Which is fine. We’ve all done that. But within that scenario, find something that sparks your curiosity, even if it’s a kernel of something, something that sparks your interest, and come to it from that angle or from that perspective, because in and of itself, it will elevate the project and it will spark that excitement that you’re looking for. And, chances are that what will happen is what you thought was just going to be work or drudgery or something that you were going to really enjoy all of a sudden becomes something that you can’t wait to get to in the morning. That’s something that I really, really try to do. Especially if I, decide to take something that doesn’t necessarily throw me. It interest me. It’s in my field. you know, but it’s kind of the money job. But, you know, if you can find something, some passion to bring to it, it will alter and elevate the entire experience for you.

Steve Cuden: Well, you’re saying something so wise and true, and it’s all about attitude. Just like the actress who came in after having won the Tony Award, her attitude was perfect. That is to say, I’m coming in, I’m going to give this my best, no matter what it is.

Robert Monroe: Right. And you can find some aspect of it that really interests you, and you come to it from that particular perspective. It may not be a perspective that anybody else has thought of. You know, it may be a point of view or, it may shift the perception of the whole project because you’re seeing something in it that maybe somebody else didn’t see. Because that’s the part of it, the small part of it, that really fills you with a certain amount of excitement and passion. And if you infuse it with that, then it may take this project to a whole completely different level.

Steve Cuden: Outstanding advice. Robert Monroe, this has been a fantastic hour on StoryBeat and I can’t thank you enough for your time, your energy, and especially for your wisdom on all this. And I wish you very well in selling many copies of Bungalow Terrace. If you’re interested in reading a great book, I highly urge you to go out and get Bungalow Terrace. Thank you, Robert, very much.

Robert Monroe: Thank you. I truly, truly enjoy this, Steve. I really appreciate it. Thank you.

Steve Cuden: And so we’ve come to the end of today’s StoryBeat If you like this episode, wont you please take a moment to give us a comment, rating, or review on whatever app or platform you’re listening to? Your support helps us bring more great StoryBeat episodes to you. StoryBeat is available on all major podcast apps and platforms, including Apple Podcasts, YouTube, Spotify, iHeartRadio, Tune in, and many others. Until next time, I’m Steve Cuden and may all your stories be unforgettable.

0 Comments