“It’s interesting, I had a friend read some of the early drafts, and I’m thinking, this is a war story. I mean, It’s World War II, it’s a war story. They called up, they were almost in tears, and they said, it was the most beautiful love story I ever wrote. And I said, no, wait a second, doctors, Colonels don’t write love stories. They write war books, okay.”

~Tom Stein

Doctor Tom Stein recently published his first book, Gratitude Is Not Enough, The True Story of a Belgian Family Forever Changed by a Band of American WWII Soldiers. The book focuses on the Remember Museum ‘39-‘45 in Clermont, Belgium which was opened by Marcel and Mathilde Schmetz, better known as the M&Ms by soldiers in a U.S. Army Company of the First Infantry Division who were briefly quartered on Marcel’s family farm in December 1944 before the Battle of the Bulge. Marcel saved many of the items the soldiers left behind, what he calls “treasure,” and which became the core of this special collection dedicated to the Americans who helped liberate Belgium from four years of Nazi occupation. The Museum, which is adjacent to the M&M’s home, contains the requisite “stuff” of a museum, but importantly, tells the soldiers’ stories, many of whom became lifelong friends with Marcel and Mathilde.

I’ve read Gratitude is Not Enough and can tell you it’s a powerfully written account of what the people of Clermont endured during World War II and the M&Ms efforts to preserve their history in their museum. I highly recommend this book to you.

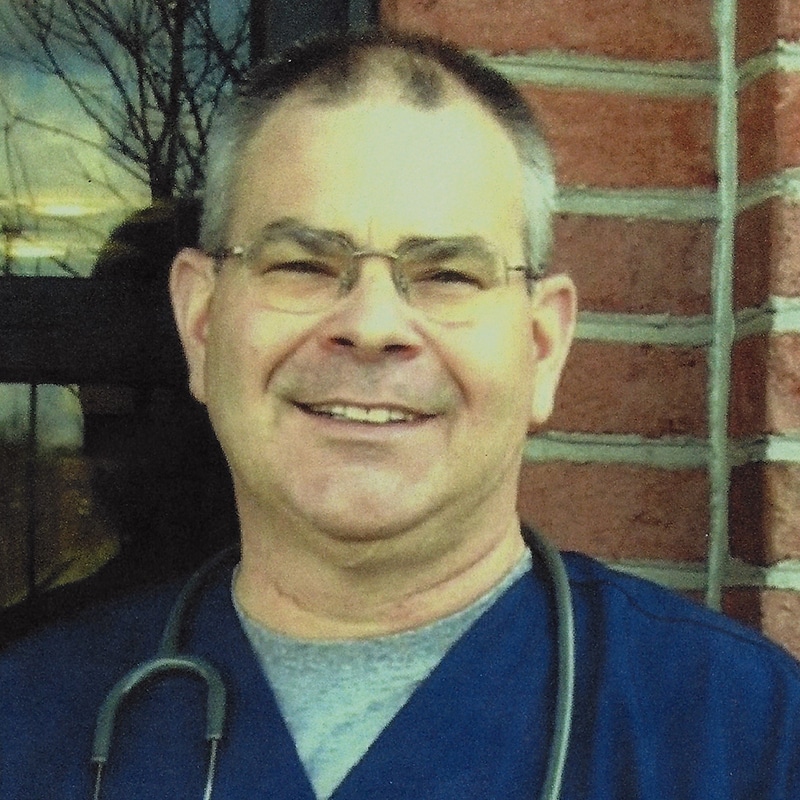

Dr. Tom Stein is a retired Emergency Physician, as well as a retired Colonel in the U.S. Army Medical Corps. He completed his Emergency Medicine Residency at Darnall Army Community Hospital, Fort Hood, Texas and served thirty-eight years in the Army and Army Reserves. Emergency Medical Services and Disaster Medicine are his sub-specialties.

WEBSITES:

TOM STEIN BOOKS:

IF YOU LIKED THIS EPISODE, YOU MAY ALSO ENJOY:

- Robert Monroe, Author-Photographer-Episode #338

- Adam Rosenbaum, Author-Episode #336

- L.A. Starks, Author-Episode #334

- Martin Dugard, Author-Episode #328

- Richard Walter, Author-Legendary Teacher-Session 2-Episode #323

- Carl Canedy, Rock Legend and Phillip Doc Harrington, Author-Episode #322

- Joseph B. Atkins, Author and Teacher-Episode #311

- Joey Hartstone, Screenwriter-Novelist-Episode #302

- Skye Fitzgerald, Documentary Filmmaker-Episode #279

- Robert Crane, Author-Episode #252

- Andrew Conte, Journalist-Author-Episode #247

- Stephen Rebello, Author-Screenwriter-Journalist-Episode #226

Steve Cuden: On today’s StoryBeat.

Tom Stein: It’s interesting, I had a friend read some of the early drafts, and I’m thinking, this is a war story. I mean, It’s World War II, it’s a war story. They called up, they were almost in tears, and they said, it was the most beautiful love story I ever wrote. And I said, no, wait a second, doctor, Colonels don’t write love stories. They write war books, okay.

Announcer: This is Story Beat with Steve Cuden, a podcast for the creative mind. Story Beat explores how masters of creativity develop and produce brilliant works that people everywhere love and admire. So join us, as we discover how talented creators find success in the worlds of imagination and entertainment. Here now is your host, Steve Cuden.

Steve Cuden: Thanks for joining us on StoryBeat. We’re coming to you from the steel city, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. My guest today, Dr. Tom Stein, recently published his first book, Gratitude Is Not Enough, the true story of a Belgian family forever changed by a band of American World War II soldiers. The book focuses on the Remember Museum 39-45 in Clermont, Belgium, that was opened by Mathilde and Marcel Schmetz, better known as the M&M’s by the soldiers in a US army company of the 1st Infantry Division who were briefly quartered on Marcel’s family farm in December 1944 before the battle of the Bulge. Marcel saved many of the items the soldiers left behind, what he calls treasure and which became the core of this special collection dedicated to the Americans who helped liberate Belgium from four years of Nazi occupation. The museum, which is adjacent to the Minem’s home, contains the requisite stuff of a museum, but importantly tells the soldier’s stories, many of whom became lifelong friends with Marcel and Maildd. I’ve read Gratitude Is Not Enough and I can tell you it’s a powerfully written account of what the people of Clermont endured during World War II and the M&M’s efforts to preserve its history in their museum. I highly recommend this book to you. Dr. Tom Stein is a retired emergency physician as well as a retired colonel in the US Army Medical Corps. He completed his emergency medicine residency at Darnall Army Community Hospital in Fort Hood, Texas, and served 38 years in the Army and Army Reserves. Emergency medical services and disaster medicine are his specialties. So for all those reasons and many more, it’s a great honor and privilege for me to welcome the author and longtime doctor of emergency and disaster medicine, Dr. Tom Stein, to StoryBeat today. Tom, thanks so much for joining me.

Tom Stein: Thanks for having me, Steve.

Steve Cuden: It’s a great pleasure. So, first of all, I have to say thank you so much for your lengthy service to this country of ours. It’s greatly appreciated. How many years in total have you been practicing medicine?

Tom Stein: I finished med school in 82.

Steve Cuden: So over 40 years.

Tom Stein: Yes.

Steve Cuden: And what inspired you in the first place to become a doctor?

Tom Stein: I was at Purdue University majoring in chemistry. And I went to an unusual chemistry symposium at Illinois State University on a Saturday morning and I missed the Notre Dame game at Purdue and there was a grumpy medicinal chemist who was first up and I thought that’s pretty cool maybe making medications and helping people would be a good way to spend my career. The first words out of his mouth were, don’t go into chemistry, go to med school. So I took his advice. I went back, talked to my, counselor, and advisor, and they said, well, you got to take MCATs you got to do this, you’ve got to do that, and I hope you’re rich.

Steve Cuden: But you had an affinity for not just medicine, but for chemistry of a sort, and you had to study all those sorts of things, so you must have understood it quite well and liked it.

Tom Stein: Yes, that’s true and it helped you skate through biochemistry in medical school. Absolutely.

Steve Cuden: So now obviously you’re currently a published author. I assume that you have some writing skills prior to writing the book. Did you work throughout your career also sort of noodling ideas on the side for books of some sort or articles?

Tom Stein: Believe it or not, no. Never. I’m a Yinzer, as you know.

Steve Cuden: Yes.

Tom Stein: Grew up in Pittsburgh. And, I write like I speak. So I was really leery of writing a book, but it was a story I felt so compelled to tell that I forced myself to write. And, the army taught me and so of the nuns back in grade school, you know, subject, predicate, direct object, keep it simple. And so I tried to stick to that formula. But ultimately, the gentleman who was kind enough to edit the book pro bono, a very good friend of mine, said if you can say it in three words, don’t say it in five.

Steve Cuden: That’s a very, very good piece of advice.

Tom Stein: He actually, although he was a journalist major, he actually, just retired from his own very, successful branding, advertising, and marketing company. And, he’s so used to writing things very terse to the point and covering all the bases in 10 or 15 seconds. Cause that’s all you get in his business.

Steve Cuden: That’s right.

Tom Stein: That rubbed off on me. And, between the two of ss, we got through the writing part.

Steve Cuden: So now you say you write like you speak, which is of course what every author tries to achieve, is to write like they speak. So in a sense, that’s called your voice on paper. But I do note you didn’t ever use the word Yinz in the book.

Tom Stein: That would have been edited out.

Steve Cuden: I would certainly hope so.

Tom Stein: I might have been able to pass it off as a French word. I don’t know.

Steve Cuden: How would you pronounce it? Yins? I don’t know. So as you started to write, gratitude is not enough, did you already think to yourself, I can do this? or was it just a complete lark?

Tom Stein: I’d say a complete lark because, the way the story came to me as that grew on me, and that was several deployments to Germany is how I got to meet this couple. And being a big World War II fan and a very amateur historian I would spend all my free time in the Ardennes in the battlefield of the Bulge, went to Normandy, of course, and some of the World War I sites. But I mostly centered on the Bulge. Cause that’s my particular area of interest. And when I stumbled onto these people, it was very interesting how it happened. It was way back in 09, I took my dad on a two-week World War II tour that was gonna cover Normany in the Bulge and one of the stops was Saive in the German-speaking part of Belgium. Our host and tour guide would bring us to dinner every evening at the end of the day and we rehash what we went over and then he’d go over the following day’s tour and be able to answer questions and ask questions. And he brought this couple that he introduced as the M&M’s to our dinner and said, these people are the finest museum in Europe. You really need to go see it. But we’re not going to see it on this tour. And everybody went, oh. So at that point I knew I’d likely be going back to Landshut in Germany again to work at the hospital, the military hospital backfilling for the young warfighters. And sure enough, I stumbled on to somebody who knew them very well and actually personally took me to their home. And I spent two nights in their home as their guest and they treated me like royalty, as they’ve done since Marcel met these guys in 1944.

Steve Cuden: Well, we’re going to get into why that is shortly as you approached the book, did you think of yourself as a historian or as a storyteller or something like that, or a journalist? How did you think of this?

Tom Stein: Great question. First, I approach it as a historian because you go to the museum, you’ll learn about the soldiers, not the M&M’s but their stories are so compelling that you start asking questions and they have all the answers to these men, their children, their wives, their grandchildren. They know what town they live in. They know when they died. They’ve been to some of their funerals. It’s an amazing relationship. So the more I learned about them, it became storytelling. No more history, even though it was history. But the story was so amazing that the more I learned – by the way, Marcel’s favorite beverage is Makers Mark bourbon, which is hard to find in Belgium, so I always take a couple of suitcases over, for him and, late at night he speaks very little English, and I speak probably even less French, but between the two of us, we’d be sipping away, and he’d tell me these stories and I mean, oh, my God, his story is more compelling than the soldier stories. And that’s when I became a storyteller. I started a lot as a historian and turned into a storyteller, and I wanted to stay true to the story.

Steve Cuden: You’re writing about something that’s real, actually happened. You’re not fictionalizing it, and you’re not making any part of it up.

Tom Stein: Correct.

Steve Cuden: So you’re still being a historian, but you’re trying to tell it in a compelling way.

Tom Stein: Yes. And I had friends who authored novels, and they said, what you’re doing is really hard, and you’ve spent a lot of time doing this research, why don’t you just fictionalize it? And my answer was, I promised the M&M’s Mathilde and Marcel Schmetz that I would keep their story straight, and they had first refusal. They had complete veto power. And anytime I could corroborate with another means to be a good historian, I would do that. So that’s what took so long. The process was a long process because I technically probably started around 2012, 2013, gathering information. It wasn’t probably until 15-16 where I realized that, I knew enough that the story had to be told.

Steve Cuden: So you didn’t know as you were gathering that information, that you were doing research?

Tom Stein: I was doing research for my own information. Not planning to write a book, necessarily.

Steve Cuden: Not planning to write. That’s what I mean is that you were trying to inform yourself and educate yourself.

Tom Stein: Correct.

Steve Cuden: That turned into something where you thought this should be told to others.

Tom Stein: Correct. And every sip of bourbon would bring on another story and my jaw would just hang. As Marcel told these stories, I said, you’re making this up. And then he’d have to bring his wife in to explain in English better, because he couldn’t. That, no, this really happened. And this is how it happened. And this is why we can prove that it really did happen. It’s like, you know, and my eyes would just get wider, my jaw would just drop lower and I’d say, oh my God, this story has to be told. That’s when I started getting in. I actually asked him permission to write their story. And they were honored. They were shocked that anybody would be interested in doing that. And I said, there are so many people that want to read this story that have been to the museum. They love your museum, but they don’t know you and they don’t know what went behind this. There’s a whole backstory to this museum.

Steve Cuden: Let’s get into that a little bit. We’ve been teasing the listeners as to what this is. Tell us a little bit about Gratitude is not enough. What is the book actually about? Clearly it’s about the M&Ms. But what’s underneath it? What’s happens in the book?

Tom Stein: Well, it’s interesting. I had a friend read some of the early drafts, and I’m thinking, this is a war story, I mean, it’s World War II, it’s a war story. They called up, they were almost in tears and they said, it’s the most beautiful love story I ever wrote. And I said, now wait a second, doctors, Colonels don’t write love stories. They write war books, okay. And she says, oh, no, no. And then she went on to tell me what I already knew, but it didn’t dawn on me that it’s a love between Mathilde and Marcel. The love between Marcel and his family. Between his family and the soldiers that lived with them. Then the soldiers that were buried just a couple kilometers away from their home and museum, all 8,000 of them that all had their own story and all died to liberate them. And I fought a long time for a title. And I realized that everybody has gratitude for things people done. And people say thank you for your service. And not my service, but especially war veteran service. That’s fine. But they transcend gratitude. Gratitude was not enough for them. They have spent their entire lives in their small fortune, I mean, not a fortune, their small budget, on making sure that Europeans and Americans never forget what American soldiers do that’s how the backstory is really one of their love for each other in the serendipitous way that got started. In addition to the love that marcel as an 11 year old boy saw as his superheroes appeared over the horizon and literally slept and ate on his farm.

Steve Cuden: And also a love story for the museum itself.

Tom Stein: Yes, their love for the museum, that is the soldiers for them.

Steve Cuden: Right.

Tom Stein: The soldiers are almost all gone. They’re still just a small handful. They’re still alive that they know well, but most of them are gone. That museum, though, has artifacts and uniforms and ribbons and awards, you know, bronze stars, silver stars, things that soldiers have brought to hope, be displayed so that their sacrifices won’t be forgotten.

Steve Cuden: And their legacy is it goes on in time.

Tom Stein: Yes, very much so. And that is why I felt I needed to write a book, not just verbally repeat the story to friends.

Steve Cuden: Of course.

Tom Stein: Cause I want the word to get out because the museum is at risk of disappearing when they’re gone.

Steve Cuden: That is of great concern, I assume.

Tom Stein: Very great for me and for lovers of the museum. Marcel’s going to be 92 shortly. Mathilde, well, I’m not allowed to say how old Mathilde is, so I can say she was born after the war. That’s what I can say.

Steve Cuden: She’s younger than Marcel.

Tom Stein: That’s all you get to say, she is younger than Marcel. So yes, that is their legacy. Their legacy to me is as important as the soldier’s legacy to them.

Steve Cuden: So just so you know, I want to go back a half a step to something you said that I love to repeat because I think it’s important for especially people who want to write or are trying to write. We as humans are really not that interested in stories about places, events or things, so when you actually said you were thinking about writing it’s going to be a war story or story about the war, the great tales are never about something like a war. They’re always about people usually in conflict with the war as a backdrop. And so that’s what we’re interested in, is people who are dealing with whatever struggles they are. And you get to that in the book where we actually learn about the struggles not only as Marcel is a young boy in the war, but also the struggles of keeping the museum going and building it in the first place and so on. That’s what’s compelling to people to read. And I think listeners should understand that. And you got at the heart of that quite well.

Tom Stein: Thank you.

Steve Cuden: So what did you think you spent most of your time on when you were developing the book? Do you think it was the characters themselves? And yet I assume you thought of them at some point as characters in your book.

Tom Stein: Yes.

Steve Cuden: Even though they’re real.

Tom Stein: And every time. Exactly. Every time I would say characters to myself, I’d say, but they’re not. This isn’t a novel. These are real people.

Steve Cuden: But they are.

Tom Stein: But they are. And they are characters. Marcel is a character. Believe me, you would love to spend an evening with him. But I see what you’re saying about the stories of the people. I think that these two, dare I say, have more patriotism, American patriotism, than most Americans that I know.

Steve Cuden: I believe that.

Tom Stein: And that, to me, is another reason to write the book. I had A World War II vet read this and then he passed away within months of reading it. He was also in his mid-90s at the time and he said, this should be required reading in every school.

Tom Stein: And I said, well, if I could do that, we’d sell a lot of books. Cause I’d have to buy them.

Steve Cuden: Yes, that’s right.

Tom Stein: But in full disclosure, all royalties from the book, anything that comes out of the book goes straight into the museum’s bank accounts.

Steve Cuden: That’s exceptionally kind of you.

Tom Stein: And I do not see that it goes straight from Amazon or Barnes and Noble whoever, and it goes straight into their account.

Steve Cuden: Right.

Tom Stein: Unfortunately, it’s not enough to buy a foundation, so to speak, and do a legacy plan, but it’s enough to help them pay the bills to keep it running.

Steve Cuden: Going back half a step again to characters. This is what makes a book readable, is the development of those characters. That’s why your book is so readable. I would not want to read a book that was just a list of things that are in the museum that would not interest me. But the characters that actually wore those things or used those things, that’s what’s interesting and what their struggles were. And in fact, you get at that quite a bit. There are also, it seems to me, a lot of big and rather intense themes in this book. Not only war, but work, death, family life, paying things back, and of other serious human challenges. Did you realize as you were writing it, you were writing this huge bunch of themes?

Tom Stein: Yes, and that was one of the largest challenges I had early on as I wrote an outline down. That’s how I got started. And you know, I had this outline and I had soldiers and I had civilians and to weave the story in a way that people wouldn’t get lost between the soldiers who were over in the States preparing for war and Belgians suffering under Nazi occupation. And then as their time frame gets closer and closer and they finally interact in September of ’44, only for the war to be over months later, May of ’45, and everybody disappears. All those guys on the farm, all the jeeps of engineers that liberated their small town, they’re all gone. They disappear or they’re buried just an hour or two up the road.

Steve Cuden: Right.

Tom Stein: And yet all those soldiers had to be woven back into the story in a way that was useful to both the M&M’s and to the soldier to honor what they did and also to honor the M&M’s for what they have done for their soldiers, as they like to call them.

Steve Cuden: So how did you think about the structure of the book? Did you struggle with that at all?

Tom Stein: Yes, I did. Like I said, I wrote the outline down first. And as I would do it chronologically, starting with the Schmetz‘ family. Mathilde doesn’t even exist until after the war. To weave her into the story, you go through the first half of the book and there’s no Mathilde because she’s not even born yet.

Steve Cuden: Right.

Tom Stein: So how in the world does she get into the story? And that’s also was one of my favorite parts of the book.

Steve Cuden: It’s one of my favorite parts of the book too.

Tom Stein: And I don’t wanna ruin it for the listeners, but, it’s a wonderful story.

Steve Cuden: Going back to what you said earlier, it’s a love story.

Tom Stein: And those two, when you see them together, it’s America first, Marcel second, as far as Mathilde’s concerned, and her a distant third.

Steve Cuden: Wow.

Tom Stein: And vice versa. America first, Mathilde second, and then Marcel third, if it’s Marcel’s perspective, but before when I say America, I mean their soldiers. And it’s not just World War II soldiers, as I try to bring home towards the end of the book, with two wars going on for almost 20 years, and almost every one of those soldiers that were wounded had to go through Germany to get home or go to Germany only to be returned back to war again. Many, many of those soldiers, the wounded boys, were taken to the museum and treated like kings by the M&M’s. For a day we were taken through the museum with personal tours and wined and dined after their tour. And they went home knowing more about the greatest generation than they knew before they went to the M&M no doubt to be taught by Belgians, no less, not by American high schools.

Steve Cuden: Well, we’re no longer very good in this country at, teaching that sort of thing.

Tom Stein: Agree.

Steve Cuden: It’s all surface-y. There’s no real depth to it, which is why sometimes a great movie will come out and you’ll get some interesting bit of history in that, but it’s not something that is, well chatted about today. We’ve got other concerns. How long did it take you to write the book?

Tom Stein: Totally from when I actually started an outline I wrote in ’21 on one of my visits there, I actually sat down and wrote out the outline with Marcel and Mathilde, and they were comfortable with the way, I was gonna do that. So I’d say from ’19 to we published in December of ’23. So four years of writing.

Steve Cuden: Four years of writing, yeah.

Tom Stein: There were so many gaps, and I wanted it to be as historically accurate as possible. Trying to track down, I wanted every soldier that was put on paper to be able to follow them from when they landed on Omaha beach until they went home after the Battle of the Bulge and then end up back in the museum, of all places, eventually to fill in all those blanks. So every soldier had roughly the same amount of, presence in the book.

Steve Cuden: Right.

Tom Stein: And trying to track down the soldiers. And unfortunately, they were all dead. I knew so much from the M&M’s because they knew these men’s stories better than their own families do because they would come and visit and they would talk. And, you know, these old vets, they don’t talk about the war with their families. They can’t bring it up to their wives. They’re ashamed or they’re scared or they overeact or whatever the case may be. But they would sit down and sometimes even cry with the M&M’s.

Steve Cuden: Why do you think they’re ashamed? That’s an interesting comment you made.

Tom Stein: From the few people that I did talk to who were combat veterans in World War II when they were younger, they did some things that in this day and age, everything’s on TV, you can’t have a soldier even remotely go off the rules of engagement without being arrested and tried. Where In World War II, there were certainly people there, but everything was so heavily censored. Things were done that they wouldn’t want their family to know, whether it was killing somebody or stealing something, because their survival depended on it. And it took away from some starving civilian, whatever the case may be these things happened almost every day for these guys, and then when they came home, they had to pretend like everything was like normal rules. So I think that’s, in my humble opinion, why many were ashamed. Because they did things that wouldn’t pass the sniff test these days.

Steve Cuden: A little bit of a sense of guilt over things.

Tom Stein: Absolutely, absolutely. Including killing enemy soldiers, and combatants in the middle of a battle. Some guys just have a hard time with that. Even today they do.

Steve Cuden: Obviously I would have a hard time with it.

Tom Stein: I think most. If you don’t, I worry a little bit about you.

Steve Cuden: I agree. That means you might have a little sociopathology going on there.

Tom Stein: Exactly, exactly. But these men, they were safe with the M&Ms. It’s an interesting thing that Mathilde wanted to be a physician, but life did not work that for her that way because of her, own personal family situation. And, she was bemoaning that fact – I don’t know if you recall this at the end of the book – but two of her favorite soldiers were sitting there with her. And, she was bemoaning the fact that she didn’t. And they told her Mathilde, you and Marcel were the best doctors we ever had.

Steve Cuden: Wow.

Tom Stein: And they were very sincere.

Steve Cuden: I do remember reading that in the book. But it is. That’s a wow moment.

Tom Stein: It is. Wow. When Mathilde told me that and when it was corroborated by a wife of one of the soldiers to know that Mathilde’s not just blowing smoke. Like I said, if I could corroborate some of these wild moments, I wanted to make sure I could. That again, those kinds of details were so hard to get. I had to literally go through the phone book, go through white pages, work through names, and cold call multiple old seller landlines to try to track on a family member of one of these soldiers to try to get more information. Cause they were gone. And if Mathtil didn’t have their address or phone number, or email, then I just had to go digging.

Steve Cuden: Would you say that was a huge part of the process? It was digging through and finding information.

Tom Stein: That was the most time-consuming research.

Steve Cuden: That was the biggest challenge you had.

Tom Stein: Absolutely. Once people are gone and you’re trying to tell the story as accurately as possible, you have to have a leap of faith in whatever anybody’s telling you at that point. It’s no longer firsthand it’s secondhand. It may be third-hand. And you know, again, you want to try it. Cause you want this story to be historically accurate and still interesting.

Steve Cuden: Oh, yes, of course.

Tom Stein: But clearly that research was with the. I mean, I went to the Carlisle Barracks, in Pennsylvania, where we have an archive, a military archive there to the National Archives, digging through unit records, trying to track down the unit movements to see how close they got to the museum property, how close they got to that pound, on Liberation Day, who was really there. and not just somebody’s memory that’s 80 years old. The memory is 80 years old. The person may be 95.

Steve Cuden: Well, Tom, you sound just like a historian.

Tom Stein: Strictly by accident.

Steve Cuden: Strictly by accident, yes, indeed. How many times did you visit the museum?

Tom Stein: Over a dozen. Over a dozen, physically. Some of those times, like, I would be there for a week. I would make a trip over to do research there with boots on ground, because, I really wanted to talk to more civilians that were in the area and not just Marcel. And I got a chance to interview probably 15 Belgians who were 88 and up, and again, and trying to corroborate their information. That was time-consuming. But getting photographs, I try to sprinkle then and now pictures throughout the book to try to bring the reader, to make it more real for them, to actually see what Marcel saw. To actually see, indeed. I hope that I did a good enough job in that regard.

Steve Cuden: I think you did an excellent job. You also put in there quite a few maps that made it very much more interesting for me in the sense that you get a picture of, you know, the landscape of things.

Tom Stein: Yeah. And the scale, the distances were not far at all.

Steve Cuden: No.

Tom Stein: I mean, a lot of these things happen. Literally. I mean, within a hour or two.

Steve Cuden: Radius, we’d be more spread out here in Pittsburgh than it looks like it was there.

Tom Stein: Yes.

Steve Cuden: Yes, indeed. So would you say that being in Landshut, Germany, where you practiced medicine in the army, would you say that was helpful to you to be already overseas?

Tom Stein: Yes.

Steve Cuden: More than living in the United States at that time?

Tom Stein: Oh, absolutely. Like I said, I spent days walking the Ardennes to get the photographs, to walk in the path of those soldiers to try to see what they saw, and to try to capture that on film, the big battle in the book. And again, it’s not like you said, it’s not meant to be a war book per se, but the culmination battle is a talent called Buenbach. And, there’s a smaller area about 1 mile south of Buenbach called Dome Buenbach and Domain. It was a farmer’s large home, beautiful stone and brick home, three and a half stories high. So it was a very domineering, object in that part of Belgium. And that’s where a lot of these soldiers in the book fought for five weeks within a couple of hundred yards in five weeks. Never going very far from a frozen mud hole, if you can imagine that. The coldest winter on record.

Steve Cuden: I cannot.

Tom Stein: And these guys lived in those holes. So to spend a couple of weeks in a barn with a roof over your head and fresh hay to lay on or fresh straw to lay on, even if the cows are passing flatus nearby, that sure, being in a muddy, wet, frozen hole, no would have felt.

Steve Cuden: Very much like a, hotel, comparatively.

Tom Stein: It was to them. And they went on to say that. They said, these are four-star accomodations.

Steve Cuden: Did anybody, as you were wandering around there, did anybody wonder what you were doing?

Tom Stein: Generally not. I think the locals are used to people that are interested in the military history, whether they’re historians or just tourists with, a fancy for World War II, I think, and especially if you’re an American, because Americans had a huge footprint in that place from September ’44 till the end of the war, we were all over that place. And if there were more of us than there were them, meaning Belgians at that point.

Steve Cuden: You already said it, but I want to dig in a little bit. You needed to actually physically be there and see it more than read about it or see footage about it or whatever. You wanted to actually breathe the air and actually have your feet on the ground in that region.

Tom Stein: Yes. And you can still see fighting positions.

Steve Cuden: Oh, really?

Tom Stein: They’re hard to make out, but they’re 80 years old and they’re still there.

Steve Cuden: Interesting. When you say fighting positions, you’re talking about somebody had a higher ground or something like that. Is that what you mean?

Tom Stein: A famous example, which is unrelated to the book, is down near Bastogne where in Band of Brothers, where Easy Company, fought the Battle of Foy. And they take off and run, Lt. Spears runs like 400 yards down right through the Germans and turn the run runs all the way back. Their fighting positions, their foxholes and mortar pits are at the treeline. And you can still see them. I mean, the years of leaves and pine needles and stuff. But people tend to sweep that stuff out. The local farmers tend to try to maintain them. In fact, in one case, they reproduced the original wood and log roof overtop to show people what it really looked like when the guys were living in the hole. To protect them from tree bursts.

Steve Cuden: And nobody has built over top of this, nobody has developed it.

Tom Stein: Well, that part of the country is very rural. Their population is relatively small and it’s mostly centered in the larger towns. So when you get out into the area where Clermont is or Bastogne, which is a relatively large town, but once you get outside the town limits, it’s pretty rural.

Steve Cuden: Now. How did you keep track of everything? Did you have some sort of a note-taking process or how did you track everything?

Tom Stein: Great question. Originally it was kind of an old-fashioned three by five or post-it notes I gather. But I went ahead and got something like Evernote, if you’re familiar with that, where it helped me collect things, put them in files and folders so they made sense. So like stories or unit information would go into here. And therefore as I’m writing and trying to flesh the book out and I’m now at this point, then I’ll go to that file and pull out those and reread and so on. So I used something like that, kind of electronic, filing system that allowed me to search on and then I could tag many different tags to different things. So I could cross-search by looking for tags.

Steve Cuden: So you set up your own form of a database.

Tom Stein: Correct. But it wasn’t a database like we think of with Microsoft’s database. It’s more just an electronic filing system that allowed me to organize all the different pieces, very disparate pieces of like I would see something or I’d do some research. And even though I was focused on A, I’d stumble across B and go, oh, get all excited, grab B and then hurry up and put it and where B belongs because I’ll forget. and then I go back and trudge along through A again. That happened quite a few times. when I was in some of the archives looking at some of the military records which was unbelievable. Some of these unit records were written by stubby pencil. If you go back to the battalion and they had a clerk and they had an old field typewriter. They’d hunt and peck finger at a time. They would typewrite the reports, but there are stubby pencil reports written in terms of the battle being pitched and back and forth and especially at the Bulge. I mean we got overrun so quickly, so fast on December 16th of ’44, that those poor guys, I mean if they had any kind of records of that battle, it’s hard to believe now the Germans kept good records, but unfortunately, losers tend not to have the records squared away as well as the winners do. And of course, a lot of things would have been destroyed one way or the other, but when it came to the American information, it was, you have to dig and it’s time-consuming, but you can do it.

Steve Cuden: But you definitely found a lot of information that’s clear from the book itself.

Tom Stein: Yes, that’s right.

Steve Cuden: So tell us a little bit about the Schmetz family and who they were and how they got to the point where during the war they reached out and helped these Americans.

Tom Stein: Marcel grew up on a dairy farm and his father, Henry, or Henri, but, Frenchy. French Henri, but I call him Henry, It’s easier. And then he had his first son was Henry Jr. And then Marcel was the second son. So they had two children. Marcel’s dad, Henry Sr. Grew up on a dairy farm as well, back in the early 1900s in rural Belgium, just like rural United States. I mean, your universe is as far as you can walk, now it’s the villages right around you, and that’s about it. You don’t know what goes on in New York City, nor will you ever find out.

Steve Cuden: Right.

Tom Stein: So they were relatively isolated, but very close-knit with their neighbors because everybody was farmers and they all relied on each other and they bartered and did things. Marcel’s father was born in 1900, so he was 18 when the war ended, the First World War ended, and he was drafted just as the war ended and was sent into the Roar as a peacekeeper and to keep, demilitarized before the Nazis came, obviously. So he was with the Germans, lived among the Germans as a peacekeeper for two years. And when he got home, he realized that Germans are different than Belgians. They think different. They’re very serious, they’re very regimented. Where the French speaking Belgians, certainly in the rural areas are very laid back and just go along to get along.

Steve Cuden: Well, we know that people who live in Maine think and act a little differently than those who live in, say, New Mexico or Texas.

Tom Stein: Yeah, well, that would be all the way across European Asia at that point. I mean.

Steve Cuden: Well, people in Maine are very different from the people who live in Connecticut.

Tom Stein: Yes, that’s true. That’s true. No, exactly right. And so he went back and started a farm. And of course his father passed on. He was on a farm in Clermont or in the suburbs of Claremont, should I say. And, his two sons were working the farm and going to school. But unfortunately, in 1933, Marcel was born and with his older brother born in ’27, so he was quite a bit older. Marcel grew up and really not wanting to be a dairy farmer. And he ultimately ended up getting a job at a local mechanic place, an auto mechanics ‘place and he kind of just, more or less was a, fall along the owner and learned as he went. And he was very artistic. His older brother was even more so. But Marcel found out that he could fabricate parts for vehicles by hand. I mean, he was very, very good at that. And those skills really became important when it came to starting the museum because he fabricates some amazing pieces of equipment that you swear are real. If you can’t go up and touch them and knock on them, you wouldn’t know that they’re not real. He has a tank destroyer coming out of the wall. It looks all the world real. He has a full-scale V1 buzz bomb hanging from the ceiling as you enter the museum. And he has an actual recording of a V1 that sputtered across, the age that was recorded by the Belgian army. You got a copy of that during World War II. And then it starts, dropping. You hear it screaming as it heads to the ground. They hear this thunderous explosion. And he has a big subwoofer. The whole part of the museum shakes this thing. It’s pretty impressive. But he does that. And so as a child, he’d like to take things apart, put them back together. He liked to fabricate, he liked to build. And that really served him when it came to the museum. The mother was a very nice lady. Again, both his parents were long gone by the time I met them. But very nice people, as, of course, Matetil would tell me. Marcel would say, they’re nice too. But you’re always going to say your parents are nice. But I understand they were very nice people. And in the book you’re gonna see what Henry and his next-door neighbor do at much risk to their own safety. Some of the things that they do during the occupation. And even more interesting is his next-door neighbor who was literally on the other side of this brick and stone house. There was a solid wall between the two, but it was a long building. One family on one side and then Marcel’s family on the other. The other gentleman was a German who moved to Belgium in 37 or so, I can’t remember the exact year. Moved into the house beside him. And when the Nazis took over, Aneed literally annexed their Part of, Belgium. He became what they called the bn, which in German means the form leader. And he was responsible for making sure all the Nazi policies were followed by the locals, which included taking everything that the farms generated and giving it to the Wehrmacht, giving it to the Germans.

Steve Cuden: And starving the people who had nothing.

Tom Stein: To eat and starving the people. And they liked their people relatively starved and malnourished because they couldn’t resist as strongly if you’re hungry and weak.

Steve Cuden: It’s an easy way to dominate people.

Tom Stein: Exactly. And they did. But this barn broke the rules quite a bit. And he, I’m sure he would have been and his entire family would have been executed in spite of all the good he did. The poor guy went to jail at the end of the war because he worked with the Nazis.

Steve Cuden: Well, he was a collaborator, and the collaborators were not well thought of.

Tom Stein: Right. Even though he, I guess he was a collaborator, but in his heart he was not. He spent a year in jail for his crime of helping the Nazis. But he helped a lot of non-Nazis escape the Nazis, much like a Schindler’s situation.

Steve Cuden: Right.

Tom Stein: And so Marcel grew up in that milieu of people helping people in spite of very difficult times. And when he meets Mathilde and again, that is a wonderful story in and of itself, he meets his soulmate even though he’s 59 years old at that point, his mantra was, and he told me this many times, he says, tom, no wife, no kids, no problems.

Steve Cuden: And he liked to work with his hand. So he would just keep busy that way.

Tom Stein: He did, he did. And he was very busy. He was like the go to guy for that part of Belgium for if you wrecked your car.

Steve Cuden: And so what possessed Henri and the family to take in the American soldiers? Was it they knew that they would liberate them or they were going to favor them because if they hadn’t, their lives would have been at serious risk.

Tom Stein: Well, if you look at the timeline, they May 10th of 1940, they’re part of Belgium is rolled over. They capitulated in 18 days. So they were really pretty much from May of 40 all the way up until September of 44. They were under the German yoke. The 1st Infantry Division, their first engineer combat battalion, which is organic to the 1st Infantry Division, is actually the unit that liberated the village of all days on 9, 1144.

Steve Cuden: Really.

Tom Stein: So September 1144 and the little town of Clermont was just a speed bump for These guys, I mean, they’re trying to get to Berlin and get the war over. They’re not stopping at every little village celebrating liberation, although this jeep was flagged on and mobbed by the locals because they were so excited to be liberated, but they moved on. Within 45 minutes, they were gone and never to be seen again. Theoretically. Then what happened is they all ran, straight across Belgium into the West Wall, or what we call the Siegfried Line, and fought in Germany and fought in what we called the Hutn Forest Campaign. It was a horrible campaign. Probably should have never been fought. We didn’t gain anything from it. But the 1st ID Infantry Division lost a lot of people, as did the 28th. And that’s when they fell back, onto Marcel’farm back into Belgium after suffering very heavy casualties in the Hurricane Forest. So it was D Company of the rifle regiment, the 26th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division, that actually bivouacked on the farm, not the engineers that liberated the town. God knows where they. I never dug deep enough, but I don’t know where they bivouac when they fell back out of the Hurricane Forest. But C Company, the sister company of D, coincidentally bivouaced in Maildde’s home town of OB Bel, which is just on the road. So you can imagine if you have 120 guys on this farm, plus the family, all trying to live in Eaton, do their business and clean up their business and so on, not to mention a livestock and so on. It gets pretty busy. If you have a division of 16,000 men, how many forms does it take? If you divvy it up at 120 at a time? So you’ve got to be scattered over miles just to bivouac a division.

Steve Cuden: Sure.

Tom Stein: When it comes off a line like.

Steve Cuden: That, it’s one of the things that’s very destructive and in war is just the overtaking of the land itself.

Tom Stein: Yes, and they were very, very fortunate. Many farms were destroyed when they went through in ’40, but the farm of the Schmetzes was relatively unscathed. Just coincidence. Just dumb luck.

Steve Cuden: And the museum itself is on that farm, right?

Tom Stein: Well, not the farm where Marcel grew up with Henry and Maria, his mom and dad, and his brother, Henry junior. That house is about one little less than a mile across the fields from his current house.

Steve Cuden: I see.

Tom Stein: When he moved out and started his auto shop, he bought a building and a house and worked out of there, but really just down the street from his parents.

Steve Cuden: So it was the same place, basically. But not the exact place where he grew up.

Tom Stein: The same suburb of Clermont.

Steve Cuden: Got it, got it, got it.

Tom Stein: Which is nothing but rolling fields and livestock. But it’s a beautiful place in a rolling countryside. It really reminds me of Pennsylvania. It does.

Steve Cuden: And how sad it must have been for them to watch everything being just, you know, chewed up and blown up and rolled over and people being killed and all that. Must have been an absolutely horrible situation.

Tom Stein: Well, it was interesting that there was a very, very rare photograph because it was forbidden to have cameras or film in occupied Belgium or annexed Belgium because the Germans didn’t want you taking photographs and give them to the enemy. But somebody hit a camera during that entire time. And when that jeep pulled into town and liberated then him on 911 44, somebody took a photograph and that photograph is in the book. And that one soldier, the surviving soldier of the six in the jeep, went back and they had a special parade and a big deal and they gave him the keys to the city and blah blah, blah. They reshot the photograph in 1997 or whenever it was with a soldier sitting in his spot in the jeep. They brought an American jeep in and all the townspeople that are still alive stood in their respective positions in the original photo that’s also in the book. It’s a wonderful shot, but they’re eating cookies and drinking schnapps where another character, a character, another person in the book, Alice didn’t. Was only two miles away and their farm was completely destroyed and bombed and tanks ran into their barn flaming and burned their barn down. It was just a couple miles away. All about the same time of day on 911 44. It’s just dumb, luck.

Steve Cuden: Just luck. Pure luck.

Tom Stein: Pure luck.

Steve Cuden: So I’ve got to ask you about your life a little bit.

Tom Stein: Sure.

Steve Cuden: Because I would be remiss if I didn’t. You’ve spent what, 38 years in the military. Did you ever run into dangerous experiences?

Tom Stein: Not really. Yah. I was in a medical corps or as we say, I’m a medical pugke. And we generally don’t get in. I mean by the time these war I was high enough ranking because I’ve been in so long that, that you just don’t stick colonels up in the front because then you outrank the line commanders and that doesn’t work. So I end up, you know, backfilling at civilian hospitals or in Germany and so on. When I was a, lean main fighting machine back in the 80s, I did work for the joint special Operations Command and did do some interesting things back in those days, but there were no wars per se. We’re just chasing bad guys around the world, terrorists around the world.

Steve Cuden: So this show, as you know, is about creative process, and you’ve given us a lot of very interesting things to think about in your journey toward making this book come to life. But I have to ask about medicine. You’re the first doctor I’ve had on the show, so how creative must one be in the emergency room? You’ve got to have a certain amount of creativity there.

Tom Stein: I thought of it many times, U. especially when I was in training, because I trained in the army that I mentioned earlier about going to medical school when I was at Purdue. And they said, well, you gotta be rich and you got to pass your MCATs and all this stuff. And so ended up the reason I was in the army is I sold my soul instead of my bank account to the army, I went through what they called the Health Profession Scholarship Program. So the army paid for medical school, and then I owed them my soul. So it was a fair trade. Though, in retrospect, it was the best option for me. And when I was in training, I used to think them as, if you remember, on the radio, they used to have these things called Ellery Queen Minute mysteries.

Steve Cuden: Sure.

Tom Stein: Well, every patient that comes in is an alley Queen Minute m mystery. And you only have X amount of time to figure out what’s going on. And you don’t know them. And, many of these poor souls don’t even have primary care physicians. They just wander in off street. Sometimes they’re near death, sometimes they’re in a lot of pain, whatever the case may be, and you just got to figure it out with very little. Now, we can cheat and get CAT scans and ultrasounds and all that kind of stuff, but, I’m old enough that I still relied on physical exam and a good history, which I guess makes me a historian. Doesn’t.

Steve Cuden: Well, it does, but I have to imagine that again, maybe you’re telling me something different. I have to imagine that as each of these folks come through the doors and you have to make this quick assessment of whatever’s going on that you at times have got to get really creative to make that calculation.

Tom Stein: Yes. and probably that the trickiest part is not the medicine part, but the human social part.

Steve Cuden: Oh, that’s interesting.

Tom Stein: That is the trickiest because some people, they don’t speak the language, and I don’t necessarily mean English, and you have to be Careful. I’m a yin, so I was able to relate to people. I’m from a blue collar family and I could relate to the blue collar people come in where a lot of physicians come from families of physicians and they don’t tend to relate with the blue collar guys as well. I mean, I think that it’s always been to my advantage to have come from that background because it allowed me to relate.

Steve Cuden: Because you could get down figuratively in the mud with them.

Tom Stein: Yes. And especially in the army, there’s lots of mud to go around.

Steve Cuden: So now I have to also imagine that working in emergency medicine is certainly at times incredibly pressure packed and at times in the military really pressure pack. I have to think that, yes, I.

Tom Stein: Think early on that’s true. I think that you develop a, I don’t want to call it a sixth sense. That’s not fair. But you start to anticipate, because you’ve seen this pattern before or you know, after 20, 30 years, it doesn’t take as much digging because you start noticing patterns. I think it becomes if you’re good at what you did and you get better because you pay attention. I think it’s not as sure if you took somebody who’s not trained to do what I did or used to do and just throw them in, of course they’d be terrified. I mean, you know, in comes somebody, your gunshot wound, they are re bleeding and they’re mfing and they’re everything. Yeah, but if, but if you do that several times a week, every week, year in, year out, it becomes kind of second nature.

Steve Cuden: So I was going to ask you that. maybe it’s a pointless question is how do you handle pressure? But maybe the answer is you handle pressure just by having gone through a whole lot of pressious scenarios in the first place.

Tom Stein: Yeah. It doesn’t feel like pressure until it’s over.

Steve Cuden: If that makes any sense in retrospect. You then think to yourself, wow, that was something unusual or big or different. Yes.

Tom Stein: Right. Yeah. Or could went the wrong way or thank goodness I did this or you know, you’re always second guessing and if you don’t have a perfect outcome, you have to learn from them.

Steve Cuden: So in the moment all that goes away. It’s only after the fact that you start to dwell on it.

Tom Stein: I would argue that most emergency physicians that are trained in emergency medicine that have done it for more than 10 years, I think that’s absolutely true.

Steve Cuden: I think that makes a lot of sense. So I’ve been having the most marvelous conversation for an hour now with Tom Stein. And we’re going to wind the show down just a little bit. And I’m wondering, you’ve clearly been through a whole lot of really terrific experiences, both positive and difficult. And I’m wondering, do you have a story that you can share with us that’s either weird, quirky, offbeat, strange, or just plain funny.

Tom Stein: From the medicine side there’s two that come to mind that always come up when people ask me. This one is this poor old soul came in from a nursing home one night. It is probably after midnight. They sent her in for she had altered mental status. And the nurse is going, jane, Jane. And the lady just laying there unresponsive, Jane, Jane. And she’s not answering. And I go up and I said, what’s her name? And here you know I’m old-fashioned, I don’t like to call my elders by their first name. So I looked at her chart and said, oh, Mrs. Smith, are you okay? She opened her eyes and said, well, yes, I’m okay. I said, why didn’t you answer me? She said because my name’s not Jane.

Steve Cuden: That’ll do it if your name’s not Jane.

Tom Stein: So that was cute. And then, oh, my God. This one poor patient came in that had, very prominent front teeth. I guess in the old days we might have called them buck teeth.

Steve Cuden: Okay.

Tom Stein: And the nurse, they were just noticeable. As soon as you walk in the room, unfortunately, your eyes would be drawn there. And the nurse is helping this patient get a gown on. And the nurse says here, she meant to say, put your arms through here. And she just. Just put your teeth through here. Oh, my God. There were two of us in a room with her, another nurse and myself. And. Oh, my God, try not to laugh. It was just. It was horrible. So that was a quirky, funny story. I have to admit that those are funny stories.

Steve Cuden: Alright, so last question for you today. You’ve given us a lot of very interesting information and tips and so on along the way as to how you did what you did in creating the book. But I’m wondering, is there a solid piece of advice or a tip that you would give to those that are starting out either in medicine or in writing, that you might find very useful?

Tom Stein: For them from a writing standpoint? Being my first book, and I’d love to write another one. my wife might kill me, though.

Steve Cuden: Nothing stopping you. Except maybe your wife.

Tom Stein: It would probably be another World War II book and it would be, again, factual. It wouldn’t be a novel. But I really think that if you find a story that is compelling, it has to be told and you will find a way to write it. Ah. Just like I did, because I’m not a writer. Just words just come out and you rearrange them and you read them and they look pretty good after the 15th time you give them to somebody else. Say, did you really need to say that? Well, no, I guess I didn’t mean to say. And, you know, it’s just like, you know, you’re firing. You don’t fire for effect right away. You got to bracket it. You know, that round’s little short, this round’s a little long. Okay, we got the rounds on target. Fire for effect. It was the same way writing. It just kept nuancing. And, again, having a good editor that was kind enough to take my Yinzer speak and put it, into normal english, was a huge help.

Steve Cuden: I would submit that you have normal english as part of your than you being.

Tom Stein: What I was going to say is we’ll go downtown to Primanti’s N’at.

Steve Cuden: And only us will understand that. No one elsewhere will understand what that means. Dr. Tom Stein, this has been a fabulous hour on story beat, and I can’t thank you enough for your time, your energy, your wisdom, and again for your service to this country. Thank you so much.

Tom Stein: Thank you, Steve. It was a wonderful time.

Steve Cuden: And so we’ve come to the end of today’s story beat. If you like this episode, won’t you please take a moment to give us a comment, rating, or review on whatever app or platform youe listening to. Your support helps us bring more great story beat episodes to you. Storybeat is available on all major podcast apps and platforms, including apple podcasts, YouTube, Spotify, iheartradio, Tune in, and many others. Until next time, I’m steve keen, and may all your stories be unforgettable.

That was a great interview with Tom Stein! I worked with Tom on the design of his book and created all of the maps. It too became very personal with the real people involved. Tom’s explanations into the backstory were excellent to hear while not giving away any spoilers. It was a honor to work with Tom so M&M could have this legacy told. Thank you Steve.

That was a great interview with Tom Stein! I worked with Tom on the design of his book and created all of the maps. It too became very personal with the real people involved. Tom’s explanations into the backstory were excellent to hear while not giving away any spoilers. It was a honor to work with Tom so M&M could have this legacy told. Thank you Steve.

Thanks so much for listening and for your kind words about the interview. Tom is a very interesting fellow, and made for a great interviewee.